Fulvio Pennacchi

Family

oil on agglomerate1938

80 x 100 cm

signed upper left

Reproduced in the book: "Artists in Brazil - Fulvio Pennacchi" - Editora Raízes, page 38.

Fulvio Pennacchi (Tuscany, Italy 1905 - São Paulo, SP 1992)

Fulvio Pennacchi was a painter, ceramist, draftsman, illustrator, engraver, and teacher. Italian by birth, this artist of great and varied prowess trained in Lucca and Florence, having studied with Pio Semeghini, a poet of light who, despite being seduced by post-Impressionist Paris, was able to reinvent his memory by countering plagiarism. Under his guidance, Pennacchi developed his capacity for penetrating contemplation, which he transformed into a firm and precise image without a trace of fatigue or uncertainty.

Armed with the seriousness of academic painting, he participated in the wave of great, pure patriotism founded on the works of the great painters of the Trecento and Quattrocento; He managed to understand and bring together the artistic conceptions of post-Impressionist Paris. He grasped the significance of the Cubist and Futurist parentheses, as well as metaphysical intellectualism, and prepared himself to produce a painting of classical origins that, according to Pennacchi himself, should be characterized by precision of line and form, as well as decisive use of color. If we wish, we can say that his aesthetic formula for this new classicism was reduced to clear ideas, proportion, modesty, and common sense.

He had a deep knowledge of the most representative of the Italian primitives, and their spirituality, sobriety, and dignity brought him closer to Masaccio and Giotto[1]; from the Novecento[2] he inherited the spatial and volumetric relationship that he would represent, after much study, in his landscapes through the solidity of the walls, the massive geometry of the houses and figures, and the anchoring of the figures to the earth[3].

Having been forced to leave the Italy of its megalomaniacs because he disagreed with the obsessive, factious, and totalitarian direction imposed by fascism[4] which, gradually dominating every aspect of Italian daily life, determined that the regime's exaltation would also be carried out through art, Pennacchi arrived in Brazil in 1929, graduating from the Royal Institute of Art Passaglia in mural art, beginning his long artistic career that, in Brazil, lasted for over 60 years, having been widely recognized by the public, government officials, and critics.

Upon arriving here, he revitalized the fresco technique, of which he became its greatest exponent, achieving a new hybrid: the happy marriage of tradition, modernism, classical values, and contemporary taste. The tradition was represented by the reinterpretation of the volumetric and spatial values of the Italian painters of the 1300s and 1400s, who, to the clear and elementary geometric volumes of the 1300s, had combined perspective, enabling the emergence of a monumental art, distinctly present in the frescoes of the Church of Our Lady of Peace and in those of large proportions.

Without ever abandoning drawing[5] and easel painting, in the serenity of his ideal of a synthetic and powerful manner, he decided, in 1937, to turn to mural painting; first in oil, and then dedicating himself to affresco[6], with extraordinary artistic results and critical success. The muralist phase would last until 1959[7]. He had brought from Italy the relative values needed to create a unified and harmonious work where architecture, environment, decoration, and graphic elements would merge into a multi-faceted project.

It is clear that Pennacchi had pondered the importance of working concurrently with the birth of an art proposed by artists united under the aegis of the Novecento, and his artistic production from that period demonstrates his acceptance of being part of that movement. But, coming from a family from which he had inherited profound Christian values, Pennacchi was more fascinated by the miracle of life and the grandeur of Creation than by the mature myth of Roman classicism, and at the same time, he was completely opposed to anyone who might support the petty-bourgeois painting of the late Ottocento. He himself wrote that, upon his arrival in Brazil, he preferred to live very modestly than to adapt my art to the tastes of the local bourgeoisie.

At just 36 years old, he produced a masterpiece: the architectural design and monumental frescoes of the Church of Our Lady of Peace, for which he conceived a project that reinterpreted the Romanesque style for the construction itself and, adopting the principles of “rappel à l’ordre[8]”, he reworked the primitive Italian style of the Tre and Quattrocento, painting frescoes that, through the sober balance of full and empty spaces, harmonize with the monumental conception of the great arches and the transcendence of the planes, creating the painting of verticals in contrast with the painting of the weight of colors[9]. Everything very simple; of modern taste with an antique flavor, where geometric rhythm discreetly encloses each figure or element of a figure.

However, his favorite themes are those taken from everyday life, unheroic, sometimes mournful, but always persuasive, forming a counterpoint to Piacentini's celebrated, iconic, symmetrical, and symbolic "lictorial style," which attempted to immortalize false classicism through false solemnity and severity; creating, instead of a legitimate reinterpretation, a caricature, so aptly pointed out by Malaparte, Rivera, and recently, by Botero.

The concomitant production of terracotta sculptures, starting in the 1950s, based on studies of local soils and clays, led to a ceramic work of unique character—inimitable!

His artistic journey in Brazil always contemplated human activity and, through it, his homage to Creation and to the "divine that every human being contains." The volume and chiaroscuro of the 1920s and 1930s, which had been used as a response to the perspectiveless surface of the futuristic cube of his formative years, was gradually replaced by the figurative and the colors present in the tropical “Fontainebleau and Barbizon”.

A reserved but highly cultured man, he also expressed himself through poetry, which, by not worrying about style or rhyme, managed to imbue his writings with musical and undulating rhythms. The text, in turn, always demonstrated the rare quality of an artist's awareness of the philosophical scope of his art.

Our legacy: As a man, Pennacchi left us the example of a life in constant construction, guided by courage and unwavering character, hard work, perseverance in the pursuit and achievement of his ideals, and love for God and his neighbor. As an artist, he bequeathed to us a body of work that reflected the archetypes of his Tuscan tradition, the rigorous and serious reinterpretation of the classicist tradition, combined with profound reflections on Creation.

Florilegio

Pennacchi is an emblematic figure of an Italian immigrant; exuberant with human and spiritual values, who without any discouragement knew how to endure and overcome the enormous difficulties encountered in his first encounter with a society that was different and indifferent to him.

A society that he, as a good Christian, neither rejected nor despised; on the contrary, he sought to understand it, and with willpower, he integrated himself into it, proud of his cultural identity, confident of being able to find common ground on which to base his energies and develop his creativity.

And the common ground was that of the human and spiritual values of the humble and simple people who, like him, fought for life, and of all those who, through the gifts of their social condition, had transformed them into means of human advancement.

Father Francesco Milini, C.S.

April, 1986.

"The most valuable lesson about good painting is to concentrate on conscious study."

Fulvio Pennacchi.

... I didn't know much about painting. Pennacchi taught me, then,

even about architecture, as he had a very good education, acquired in Italy,

and had been painting for many years, since before 1930... we would go out together to paint landscapes from nature, and while he painted, Pennacchi spoke with great humility about his painting. This humility he preserved forever,

contrasting with the great presence and power of his painting.

Francisco Rebollo Gonçalves, 1935.

... the young and valiant Italian painter, unlike others, does not dramatize the obscure misery of men in violent tones, but seeks to idealize it in a superior, almost religious atmosphere. Pennacchi's workers and peasants are not revolted against their own fate or against anyone...

... he is a religious painter not because he enjoys painting sacred episodes, but because of that mystical sense that shines through in his compositions, always admirable in their balanced distribution and frankly modern technique.

... he belongs to the few who know how to blend the materiality of modernly realized form into a new atmosphere, unreal without being romantic, mystical without being obedient to any ecclesiastical convention.

... a delicate poet with a vigorous imagination, an idealizer of anonymous and simple life, an artist who, in the visual arts of figures, knows admirably how to interpret the intimate feelings of the characters he depicts. Pennacchi thus constitutes a rare exception in the field of art; his studio and works are a restful oasis in the chaos of contemporary painting, which reveals one of its most complete, original, and sincere expressions.

Franco Cenni, 1936.

... the small works, precious gems that Pennacchi exhibited in the Arcades, were greatly admired, and many mature and serious painters paused before them and reflected at length...

... drawn with a clarity comparable to that of a writer with a vast descriptive capacity, these rural scenes have as intrinsic components something ancient and a great deal of realistic intensity, where the polychromy of the skies and the curves of the hills reflect a sufficiently mystical and profound appearance that we imagine a world fertilized by a new deluge that reborn it with greater harmony and radiance, as if it were the result of a gust of wind. cosmic cataclysm.

...Pennacchi is among the artists who combine sources from the great painting of yesteryear with controlled infusions of modern plasticity. The importance of the figure in his work has been observed. The landscape itself functions in him not as an aesthetic act in itself, but as a scenographic plane inseparable from the being that populates and transforms it.

His compositions with multiple characters are a Tuscan heritage of forms and planes that construct a balanced perspectival space. They result primarily from agile drawing, but he also demonstrates sophisticated knowledge of color and materials.

Francesco Piccolo, 1936.

...I'm getting closer to your spirit, in which I see an old woman

animating a path of renewal...

I think there's a lot of Modigliani and Kisling in your painting,

but you're always a liberated and interesting Pennacchi.

...now I'm certain of your definitive and imminent triumph.

Jorge de Lima, October 1937.

...a continuous and perfectionist work of a muralist marked Pennacchi's production, attracted by fifteenth-century humanism.

...Pennacchi stands out, on the one hand, for the definitive influence he received from ancient Tuscan painting as a young man; and, on the other, for its contrasting themes of sacred and profane subjects.

The emphasis placed on the human figure also distinguishes him from most Santa Helena artists, who focused more on landscapes.

The landscape element is important to him, but the artist essentially reserves it for a supporting role.

... the Santa Helena Group, a spontaneous gathering of humble workers,

almost all semi-laborers in the field of visual communication, entirely outside the official and elitist process in which Brazilian modernism developed.

(...) is the affirmation of a great personality. His spiritual and expressive paintings constitute magnificent interpretations of states of mind, especially religious sentiment.

A Gazeta, 1944.

(...) it is noteworthy that in the still lifes presented, the use of chiaroscuro provides a truly remarkable aid.

With this aid, the painter gives his paintings, within a grip of color, volume, and free drawing, a truly admirable artistic depth of mastery.

Quirino da Silva, 1944.

(...) it is undeniable, however, that the artist knows how to compose a painting like few others. And that he feels at ease in both large and small compositions. He is by no means a banal painter, but rather a professional who knows his instrument well and uses it with ease and skill.

Ciro Mendes, 1944.

Fulvio Pennacchi is a well-known artist among us. He began painting fresco murals of a religious nature in the Church of Peace. These famous decorations alone are enough to immortalize the young painter's name. (...) although most of Pennacchi's works are religious in nature, it is clear that he also feels our rural landscapes with great emotion.

Dr. Osório César, 1944.

(...) the most interesting is, without a doubt, that of the painter Fulvio Pennacchi. Above all, for the note that best characterizes it, the high spirituality of the compositions.

Pennacchi is a talented artist with a great personality. He is not a realist, concerned with reproducing nature as we see it, but an interpreter who gives expression to ideas and feelings.

To create this work, Pennacchi eschews conventional processes without falling into the excesses of modernism, reconciling the classical and the modern, in order to arrive at a form of expression suited to his personality... and he fully achieves his goal, in a series of excellent works that place him among the true values of modern São Paulo painting.

(...) a painter attentive to the problems of painting, attacking still lifes and flowers with purity.

(...) eschewing the comfortable formula, the painter achieves subtle, delightful solutions of great taste. We must also praise his conscientious drawing, which constitutes, perhaps, the best quality of this painter who exhibits successfully in the Itá building.

Sergio Milliet (da Costa e Silva), 1944.

Fulvio Pennacchi is a painter.

His work, especially the murals and frescoes, reveals that his artisanal awareness was not acquired through praise and easy permission.

Almost a life dedicated to work consumed him as a painter. Unbelievable setbacks marked his arduous pictorial journey,

while some of his generation embraced mystification.

It is much more comfortable, easier, even profitable to respond to the avant-garde demand...

Quirino da Silva in, Diário de São Paulo, 12/6/1944.

(...) Pennacchi has not exhibited for a long time. During all this time, he was kept away from the fuss that improvised critics were making about his "favorite artists." Now, it's no longer possible to keep them on the bill, as a careful review of values has begun.

(...) thus, the true artists began to reappear, as if to tell collectors and the public what they did during all this time while the hype was boiling.

(...) so-called modern art in our land also owes much to Pennacchi.”

Quirino da Silva, 1964.

(...) an artist's retrospective is history. The painter we honor today is already in those pages. A fresco artist, illustrator of life in the rural villages, of the time he traveled there, portraitist, ceramist, master.

(...) possessor of scrupulous professionalism, Hardworking, without leisure, isolated, and strong in avoiding the easy noise of the babbling and tiresome publicity, renouncing commitments that were not appropriate to his own conscience, firmly pursuing his moral ideals.

Fulvio makes us think of those artists from his homeland who, honest and persistent, devoted themselves to their work without being impressed if their ways might seem outdated.

Pietro Maria Bardi, 1973.

(...) when he saw his retrospective, it was easy for all who doubted the strength of his work to recognize a little of the creative capacity of this tireless artist in crafting an angelic creation based on our own regionalism... these are the paintings of a master, of a profound connoisseur of composition.

Ivo Zanini, 1973.

He conveys in religious scenes the humanity of the saints, not to diminish their sanctity, but to unite them with men.

Aldo Bonadei, 1973.

... Pennacchi's painting is neither realistic nor primitive in the easygoing manner of so many feigned naive people who use it to disguise their congenital inability to paint: it is a poetic transfiguration of reality.

... in a happy context of colors, gestures, and attitudes from which emerge images internally recreated from the things observed, a meditated harmony induced in the unconscious disorder of natural aspects.

This is, and always has been, the essence of art.

Emilio Mazza, 1973.

There will be moments of faith and poetry:

an exhibition of 27 paintings by Pennacchi,

which are not included in the catalog because

it is a tribute from the Collectio to the artist.

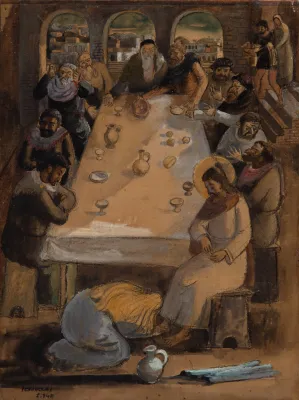

Country Lunch , a work that Pennacchi painted in 1939, which is a lunch after a harvest,

but which inspires the same respect as sacred paintings

of the Last Supper, is one of these works.

Collectio in O Estado de São Paulo 26.08.1973.

The gold of the medal that we now award must have the meaning of a great lesson. In the unsettling atmosphere of the modern world,

that (the medal) teaches everyone

how it was done yesterday, how it is done today

and how it will be done undeniably and inexorably tomorrow...

how to achieve an ideal,

to force life to say yes when it says no,

to circumvent difficulties, overcome life's pettiness,

to remove obstacles... to achieve success step by step!

Minister Togni, Lucca, August 1973.

The Alberto Bonfiglioli Gallery begins

the year 1974

very well

with this exhibition, almost a document

in Pennacchi's artistic life...

an exhibition that stands out not only for the diversity of themes

and techniques it presents, but also for the human dimension it highlights. covers.

...Almost always suggesting form through color, he manages

to detach himself from the designer he is, sensed by the observer,

in the richness of the composition's details...

He achieves pictorial fullness in the striking presence of the mood captured by color, in a refined, detailed study of atmospheres,

close to the purely ecological.

Lucio Galvão in, Natureza marca obra de Pennacchi,

O Estado de São Paulo, March 1974.

Fulvio Pennacchi is modesty personified.

I consider his work and his research in art more important than his social prominence. He consciously placed himself in the shadows, offering men the brilliance of his works, which he always surrendered to God.

Jornal de Brasília, August 30, 1974

...after studying since 1973 a mixture of clays and metallic dyes and a firing process that would not break or warp the fine panels...above all, what stands out in his luminous panels, from the serenades in Diamantina to the processions in Ouro Preto, is the result of a laborious and impeccable technique, allied with man and the Brazilian landscape.

See Magazine, September 1975.

Pennacchi: for the first time in Santos

Lyricism, purity, hope, harmony, and serenity...

Pennacchi conveys all of this to us through his work...

so many in both large and small works!

City of Santos, September 11, 1977.

... the exhibition that Pennacchi opens tonight

attests to the sensitive traits

(...) although born in Italy, Pennacchi fell in love with his adopted country

to the point of representing it almost systematically in his work...

of an artist who soon assimilated the Brazilian way of life,

capturing all the colors and domestic scenes of Brazilians,

especially their folkloric traditions.

Ivo Zanini, April, 1979.

... but he took me to Our Lady of Peace, a beautiful church of imperishable modernity (I think the construction dates back to the 1940s), featuring a bell tower of romantic lightness and boldness and frescoes by Fulvio Pennacchi that move me far more than any Saint Francis by Portinari.

Mino Carta in, São Paulo Renews Itself, Despite the Powerful - Folha de São Paulo, January 21, 1982.

It is worth highlighting the extensive mastery of drawing, the harmony of colors, and the richness of detail in his work:

Despite exploring primitive themes, he cannot be classified as naive, as his figures are free of any abnormalities and his technical skill is always visible.

Artist Roberto Camargo in, Visão, July 1985.

Pennacchi has been, for the last twenty years, a lyrical storyteller... delicate, soft, lightly colored! It would be entirely wrong, however, to confuse his delicacy, gentleness, and lyricism with any kind of primitive naiveté. Fulvio Pennacchi is a very learned painter, in the best sense of the word. His simplicity is the choice of one who has completely mastered the craft.

Olívio Tavares de Araújo; "Soft Filigrees of a Master," April, 1980.

I really like Pennacchi's luminous simplicitas: his way of seeing and showing things.

Josef Piper, 1986.

(...) Pennacchi's hand doesn't tremble, his eye remains sensitive to color. The atmosphere throughout is serene and respectable.”

The concept of simplicitas, central to the classical tradition of Western thought, refers, first and foremost, to the Gospel saying: “If your eye is single, your whole body will be full of light” (Matthew 6:22).

Such a simplicitas of the spirit is a condition for grasping the object, the source, and principle of authentic art and philosophizing.

Prof. Dr. Luiz Jean Lauand, 1986.

The night is rich, even in the favela. The central, dominant balloon, surrounded by children. The hill, rising in the background, slopes of shacks. And trees, and lampposts, and chickens pecking. In the popular world, life is always filled, including the celebrations that naturally mark it, joyfully.

The message is clear: living is never tiring.

Ricardo Ramos in The Rediscovery of Brazil

Exhibition at Ranulpho Art Gallery, São Paulo, 1987.

(...) It is rare for an artist to be clearly aware of the philosophical scope of his art: a painter paints and does not philosophise. Philosophical reflection deals with concepts; art, with sensible and concrete forms.

However, there are exceptional cases of painters who break the reality-sensitivity-work of art circuit. They expand it: reality-sensitivity-work of art-reflective consciousness. This is the case of Fulvio Pennacchi.

I have always been surprised by the way this painter addresses the complex philosophical-theological concept of Creation, which is indeed central to his art.

(...) Vita e Amore, a poem composed by Pennacchi in 1942, exceeds any and all expectations of being in tune with the most essential teachings of the Western tradition of thought regarding man... Happiness and contemplation, happiness is contemplation: this is a thesis on which the four greats of the Western tradition unanimously agree: Plato, Aristotle, Augustine and Thomas. (...) This is precisely what is evidenced by Pennacchi's paintings and ceramics (and I am not referring here to the sacred artist): knowing how to see simple, everyday reality... and discovering therein the very foundation of the world: everything that is, is good; it is love for God. And what's more, it's because he's loved by God.

(...) And Pennacchi expressed it almost 50 years ago:

Vita e Amore

How I love to see;

around me everything is always new,

The people who pass by and play are always new,

And cry and smile: the dog barks,

The tree bears fruit, the birds sing happily and noisily,

I like to be alone, contemplating at leisure the eternal beauties of Creation,

If I read, I imprison myself in a world, made by a man,

Free, how beautiful, to be in the countryside,

to live in the world of the Creator,

A world that often seems sad,

But which in essence is all made of love!

Prof. Dr. Jean Luiz Lauand, in Fulvio Pennacchi: 60 Years of Painting and Wisdom, O Estado de São Paulo, March 24, 1987.

(...) knowing that his illness had worsened, I went to visit him with Father Cláudio (...) he was lying motionless in bed, serene, silent, and prepared for the big step. We prayed much and gave him the Blessing of the Sick.

At his side, ever attentive, was his faithful wife, Filomena Maria, who gazed upon him with great dignity and sweetness with the eyes of her first enchantment.

Father Orazio Cappellari, August 1992.

Always preserving his solid Italian upbringing, Fulvio Pennacchi was profoundly Brazilian: not only because he lived here for 63 of his 87 years, but mainly because immigration brought him to a country where the common people spontaneously live (or lived...) realities and values...

tailored to his unique artistic sensibility;

simplicity, fraternity, welcome, celebration, love.

He identified with Brazil, which provided him with the raw material for an original and profound art; His paintings are something like delicate chorinhos composed by a classical scholar.

Professor Doctor Luiz Jean Lauand, October 1992.

...curiously, Pennacchi understood and captured an authentic side

of Brazilianness, including its social aspect:

his farmers are often tired,

but there is more resignation than rebellion in them.

The enduring elegance in Pennacchi's painting,

with its refined colors

and with the very artisanal know-how that always seduced him...

in any case, the whole is limpid,

as limpidly as the painter's personality

and character are revealed.

Olívio Tavares de Araújo in O Estado de São Paulo, October 6, 1992.

Pennacchi was the religious reserve of the group (referring to the Santa Helena Group) A craftsman trained by the Lucca Academy, capable of keeping the tradition of mural fresco alive; The Italian painter reworked the syntax of Renaissance painting. Moreover, he was a kind of Tarkovsky of painting, capable of moving the atheist world with his untimely figures of saints. Antonio Gonçalves Filho, 1995.

... there, the house surrounded by gardens is the nostalgic reconstruction of a lost Tuscany, it is the anxious embodiment of the desire to recover the silence of the old Florentine mansions...

Pennacchi not only creates the residence and fills it with his frescoes, almost always of pious and almost always Italian themes.

No: he conceives the main furniture, his most everyday utensils, designs the themes of the pillows, towels, and sheets that his wife will later embroider.

His residence, conceived in its entirety, is undoubtedly the culmination of the artist's work, a moment in which he expands the allusive spatiality of his pictorial work into concrete reality.

As far as we know, no other artist in Brazil was as radical as Fulvio Pennacchi in this endeavor to aestheticize his own life.

His idealized Italy, more so than in his Sant'Elenista phase, increasingly took on a Brazilian feel. His later works attempted to recreate, visually, an ideal country—a blend of the distant land of his parents and the new land of his children!

Prof. Dr. Tadeu Chiarelli, 1999.

Talent became flesh and dwelt among us. His name was Fúlvio Pennacchi (1905-1992), and he would have turned one hundred two days after this Christmas of 2005. In him, the word became image and became life and dream.

In 1942, he gathered around the announced child, the angel, and the shepherds of the Nativity in the presbytery of a new church nestled at the foot of Piratininga Hill. The place where the poorest residents of that isolated stretch of lowland land in the proletarian Brás lived and still live. It was so that they could witness once again the birth of the Son of Man, there in the Church of Our Lady of Peace, at 225 Glicério Street, among slums and ruined houses, streets that time would populate with homeless people, those with nowhere to lay their heads, paper collectors, garbage recyclers, often treated as refuse themselves. Those whose eyes no longer hold tears, whose time no longer holds the consolation of hope.

The Church of Peace is the church of migrants, of those seeking a place in the world, the church of Saint Paul where the Nativity is perpetually celebrated and, amid the poor, life is proclaimed, hope proclaimed daily in the beautiful frescoes on its walls. In the others, the suffering Christ of the bloody Passion takes precedence.

In the church of Glicério, the Christ of the simple does not accuse our conscience. He invites the heart, of those who believe and also of those who do not believe, or believe differently, to communion and peace. He is the Christ of conciliation and innocence. It is impossible not to return there to contemplate that mystery in silence. Pennacchi did not summon the Magi of the Gospel of Matthew, who came from the East bringing frankincense, myrrh, and gold for the newborn. He chose the Gospel of Luke, to find the night shepherds around the Baby Jesus, Mary, and Joseph. Among those visiting the destitute child resting on the nothingness of the ground is a woman with a child in her arms. She is the last of the last in the mural, the reminder of the prophecy of our Divine festivities, that the king will be born of the people.

In the beautiful fresco, there's a gospel according to Pennacchi. This inspired Tuscan from Villa Collemandina, Lucca, Italy, came to São Paulo in 1929 to try his luck. He had been a student at the Royal Institute of Fine Arts in Lucca. In São Paulo, with his brothers, he owned two butcher shops. That's how he made a living. Six years later, he was one of the first members of the Santa Helena Group. He shared a room with Rebolo in the building on Praça da Sé.

His work contains precise symbols of his conception of the Brazilian people: the guitar and the guitarist, the country dog, the chickens in the yard, the flag of a June saint on the pole, where, by tradition, the first ear of corn, the first harvest, the first fruit of labor and the land, the offering, is hung. A skinny dog listens attentively to the guitarist in a detail of the frescoes at the Hotel Toriba in Campos do Jordão, appreciating his slice of music. Pennacchi softened the colors and shapes of Brazil to proclaim the beauty of the simple.

José de Souza Martins

Professor of Sociology at the Faculty of Philosophy of the University of São Paulo

A few years ago, on the occasion of the exhibition commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of Pennacchi's arrival in Brazil, I wrote: ...through his sensitivity, talent, and simplicity, Pennacchi became the visual interpreter of the poetic and bucolic world of humble country folk.

Today, I understand his life and work better, and I would say that he was an interpreter of country and city life. Revisiting Goethe conceptually, Pennacchi certainly did not wander through tropical Barbizon and Fontainebleau, either out of the illusion of arriving somewhere or of discovering something new. He came here to live while traveling, to understand what he saw, to contemplate, and to shape the discoveries afforded by his experience.

Fulvio Pennacchi's life and work is the experience of discovering his Brazil, absorbed and decoded through the lens of the universal, the eternal.

Valerio Pennacchi.

Annotated Works

Like the other sections, this one will also be updated as new works for comment become available.

Motherhood

; pencil and charcoal on paper; 58x41 cm; 1938

Reprinted in the book Ofício de Pennacchi on page 107

Valerio Pennacchi-Pennacchi, 2006.

Work by Fulvio Pennacchi[10] from 1938. It is a drawing on paper made in pencil and charcoal, typical of the early 1900s, but with a distinctly Masaccesque flavor, which perhaps represents, within Pennacchi's work, the most faithful continuation of the ephemeral art movement known as "Return to Order[11]," which Pennacchi brought to Brazil in 1929[12], which was probably unknown among us due to its short duration and the longer delay in the dissemination of information.

All that Brazilian artists and intellectuals (most of whom could not travel to Europe; and those who did travel went almost exclusively to Paris!) had was information about the Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, and the School of Paris, which was precisely what the "Return to Order" and the wave of European Neoclassicism brought into question within the advancement of modern art.

Those who attribute the origin of the "Novecento" movement to the "Macchiaioli" are mistaken. No! The enigmatic classicism of the "Return to Order 1919-1925," which would later flow into the Milanese and Italian "Novecento," drew inspiration from the reinterpretation and reinterpretation of Cimabue (1240-1302), Giotto (1267-1337), Masolino da Panicale (1383-1440), and Masaccio (1401-1428), invigorating architectural compactness, three-dimensional solidity, precision of form, and laconic composition. Aren't those the elements present in this "Maternity," as well as in most of Pennacchi's works during the first decades in Brazil?

Supported by Sergio Milliet and Mário de Andrade, this "return to order" in Brazil was considered "a realistic regression," and its members were classified by Geraldo Ferraz as "traditionalists and defenders of the artistic carcamanism of São Paulo," dying of love for the processes of Giotto and Cimabue[13].

And our work? I think it's a museum piece, not because of its grandiosity or subject matter, but because of the clear interpretation of the principle that guided the "return to order," which, in the understanding of the European and Italian intellectual avant-garde of the time, was based on (a) precision of composition, whose essentiality of the subject was subject to a purist simplification, (b) the decisive choice of color sobriety, and (c) the firmness of the line that was supposed to eliminate scenic uncertainty; elements that Pennacchi would embody, a few years later, with apparent ease and naturalness in the grand frescoes of the Church of Peace and in those of his own home!

The Madonna/Mother stands, draped in a wide drapery that conceals the forms of her body. The profile of her face has a severe and distant majesty that departs from the usual softness and sweetness of typical Florentine "madonnas." She does not look at her "Son"; her face seems to peer beyond the visible, as would happen with the impassive and impenetrable deities of archaic Greek art. She does not feel the strong wind that bends the sturdy tree and hinders the passage of passersby. Her thoughts are far, very far away, contemplating eternity and completely detached from earthly things. Neither the great arch nor the elements in the background can divert our attention from the serene, austere and dominant figure that, despite the relatively modest proportions of the drawing, seems enormous to us and arouses in us feelings of fear of the gods much more than love for the Mother of the Savior.

This phase of Pennacchi's artistic life is as little known as it is important. That is why I have been working for the past year (circa) on a monograph that focuses on the FP the draftsman (1915-1920), the FP the academic (until 1926), the FP the naturalist following in the footsteps of Antonio Pio Semeghini (his teacher in Lucca, whom he replaced when the latter retired to lead the "Naturalist Group of Burano") and; Finally, the artist from Lucca and Florence revisits the work of Ottone Rosai – already one of the pillars of Italian culture during the "Novecento Tuscan" – Sironi and Carrà and, through them, begins to reread and reinterpret how the "Group of Seven[14]" sought to rehabilitate Italian modern art by replacing Afro-Picassian nudism and the constitutive Cubo-Futurist divisions of Post-Impressionist Paris.

The Country Wedding," ost – 1942

Valerio Pennacchi-Pennacchi, 2009.

1942. Pennacchi had been in Brazil for 13 years. Although he had not yet had the opportunity to hold a personal exhibition, some of the main obstacles the artist encountered in a different and indifferent society had already been overcome.

The work: The parish priest, having finished his assignment, talks to a A parishioner completely oblivious to the wedding procession accompanying the bride and groom to their destination. The boy, on the left, answers the call of nature and also stands apart from the main scene, creating his own narrative. Above all, we see the large architectural volume of the church, which, with the support of the other four, maintains the entire work in balance.

This work, which perfectly synthesizes Pennacchi's painting through the presence of volume, balanced composition, and conscientious drawing with a confident line, presents us with a bonus: the explosion of colors, indicating an atmosphere of spring and happiness, in addition to the thirty characters with a caricatured address that will become more important in future years. The overflowing joy reminds us of the festive month of May in the Northern Hemisphere, certainly still vivid in the artist's memory at that time.

The volume and chiaroscuro of the 1920s and 1930s, which had been used as a response to the perspectiveless surface of the futuristic cube of his formative studies, was gradually replaced by the figurative and the colors present in Tropical Fontainebleau and Barbizon.

True to his artistic journey, he also contemplated in this work one of the many aspects of human activity and, through it, his homage to Creation and the divine that every human being contains.

The work "The Country Wedding" that we refer to interprets and records a moment in life in a human and, above all, witty way. It shows that Pennacchi did not journey either with the illusion of arriving somewhere, or to discover something new. He lived as he traveled, understood what he saw, contemplated, and shaped the discoveries afforded by his experience. He painted what was close to him.

Another way to portray the same scene would be to give it a pessimistic connotation regarding human destiny and find a way to exalt the values of civilization denied to the humble and poor participants in the scene! The tone would have been one of greater social criticism, which would certainly appeal more to those who want to make art another instrument of social denunciation, but who, at the same time, are unable to to finish off the pyrotechnic verbiage with constructive actions.

Pennacchi chose the path of apparent resignation and naivety; but he clearly recognizes the problem of human suffering and pain, when he states in one of his poems.

...maschera di riso, ognuno nel suo sorriso nasconce il suo dolore!

(…mask of laughter, each one hides his pain in his smile!)

We would still say that Pennacchi was an artist with a great and varied productive capacity; Educated in Lucca and Florence, where he had the opportunity to study with Pio Semeghini – a true poet of light, seduced by post-Impressionist Paris and capable of reinventing his memory without the danger of plagiarism – with whom he developed his capacity for penetrating contemplation, which transmuted into a firm and precise image without any sign of fatigue or uncertainty.

Having been forced to leave the Italy of its megalomaniacs because he disagreed with the obsessive, factious, and totalitarian direction imposed by Fascism, which, gradually dominating all aspects of Italian daily life, determined that the exaltation of the regime should also be carried out through art, Pennacchi arrived in Brazil in 1929, graduating from the higher art course, specializing in mural decoration, at the Royal Institute of Art Passaglia. He began his long artistic career, which, in Brazil, lasted for over 60 years and was widely recognized by the public and collectors, by government agencies, and by criticism.

Arriving here, he revitalized the fresco technique, becoming its greatest exponent, achieving a new hybrid: the happy marriage of tradition, modernism, classical values, and contemporary taste. Tradition was represented by the reinterpretation of the volumetric and spatial values of the Italian painters of the 1300s and 1400s, who, to the clear and elementary geometric volumes of the 1300s, had combined perspective, enabling the emergence of a monumental art, distinctly present in the frescoes of the Church of Our Lady of Peace and in the large-scale frescoes in private homes.

However, his favorite themes are those taken from everyday life, unheroic, sometimes mournful, but always persuasive, counterpointing the celebrated, iconic, symmetrical, and symbolic "lictorial style" of Piacentini, which he attempted to immortalize through false solemnity and severity, false classicism; creating, instead of a legitimate reinterpretation, a caricature, so aptly pointed out by Curzio Malaparte, Diego Rivera, and recently, by Botero.

The concomitant production of terracotta sculptures, starting in the 1950s, based on studies of local soils and clays, led to a ceramic work of unique character—inimitable!

A reserved but highly cultured man, he also expressed himself through poetry, which, unconcerned with styles and rhymes, managed to imbue his writings with musical and undulating rhythms. The text, in turn, always demonstrated the rare quality of the artist's awareness of the philosophical scope of his art; a consciousness masterfully understood and explained by the Brazilian Catholic philosopher and thinker Luiz Jean Lauand[15].

He lay in the shadow of the dark pit, lifeless;

Martha and Mary consumed by grief, no longer at peace;

Jesus arrived –

(....)

And to Lazarus he called with a friendly voice,

“Lazarus, come, arise and walk.”

Immense astonishment, terrified crowd, open mouths,

(...)

And in the human heart the miracle is performed by the divine power

of love, of the kindness of the generous heart of the Lord.

The Resurrection of Lazarus, ost, 1942

Fulvio Pennacchi,

Resurrection of Lazarus; June 30, 1942; 9:15 AM

The painting in question – The Resurrection of Lazarus – vibrates with warm colors: reds, scarlets, blues, warm grays, intense greens; a complex that transmits heat. The figures move, electricity permeates the air, so many things happen that cause wonder and amazement, superhuman forces act, Jesus is the power that dominates the scene – the landscape is filtered through the figures, the power of God makes everyone tremble, and transforms them all into humble men of this poor world. Pennacchi said: "I believe this painting is one of the finest achievements I have ever conceived – there are stylistic exaggerations, but the air, the atmosphere, the passion begin to penetrate both inside and outside the figures..."

Undoubtedly one of Fulvio Pennacchi's most dramatic works of the 1940s. It is not a very recurrent theme in religious iconography. Few known examples include the fresco by Gian Giacomo Testa (1582) and a fine and large work by Michelangelo Merisi, ovvero, Caravaggio (1608-1609). The episode, in this case linked to Christ's compassion for the grieving sisters—Lazarus had already been dead for four days—should not be considered solely from this perspective; but mainly because during his earthly life, Christ affirmed "that he was the light, and by his present example, he also demonstrated that he was the resurrection and the life"!

A large-scale work with approximately 30 dramatic characters, "Resurrection"; One of the last examples of his revision of "chiaroscuro" painting (painting with contrasts between light and shadow, creating a tonal perspective where the figures in the background are much more defined by tones than by contour lines), closer to 15th-century Italy and Flanders than to the Mannerist and Baroque styles of the 16th century.

The predominance of dark tones is broken by a luminosity from an unidentifiable source from the left of the work, presenting the preeminent figure of a serene and luminous Nazarene, whose colors contrast with those used in the scene. His imperious gesture with his right hand denotes energy, but as in the poetry composed concurrently with the painting, his countenance and "friendly voice" eliminate any domineering and arrogant authoritarianism.

Completing the composition is a sad and haunted crowd and a deliberately static Lazarus, attended by two of the apostles, impeded in his movements by the numerous strips of cloth covering his body. body.

A Country Family, ast, 1973

Valerio Pennacchi-Pennacchi, 2009.

The surroundings of the village, where a June festival had been celebrated some time ago, serve as the backdrop for an imaginary photographer to immortalize the proud peasant family's act of posing, gathered around their "patriarch," who displays a semblance of the peaceful and honorable life he has led...

This is how a story could begin, based on the nineteen figures, the houses, the chapel perched on the top of the hill, the walls, and the gentle slopes of the hills that clearly define that rural landscape. The relaxed complement to that dreamlike atmosphere is given to us by the intense light and luminosity of the blue sky that, in the distance, covers the mountains that take us to infinity with an almost invisible veil.

The work is dated 1973. 1973 is also the year of the MASP retrospective. After 44 years in Brazil, Pennacchi is at his best. Gone are the days of his arrival in Brazil and his efforts to endure and overcome the enormous difficulties encountered in his first contact with a different and indifferent society. He had been "discovered" in 1936 and awarded many prizes. He was one of the main protagonists of the Santa Helena Group, a friend of his fellow painters, and revitalized the fresco technique among us with diligence, energy, and dynamism. And, with the same determination, he withdrew from the artistic world in the 1950s because he disagreed with "its chaotic development." He continued to work, delving into the world of modeling malleable substances, creating volumes and reliefs with a polychromatic finish – ceramics – and finally, after about a decade, he returned to the market, applauded and revered.

The Italian painter of the 1930s gave way to the European of the 1940s, gradually transforming into the Brazilian interpreter from the 1960s onward. The work we see speaks to us of the harmony present in the world through the restoration of peace, and the persuasive balance of colors is only possible as a consequence of a utopian aesthetic palingenesis.

The artist's work remains true to his understanding of the simplification of beauty and timelessness. Far from any eccentricity of ephemeral fads, it showcases "know-how."

Solo, Collective, and Posthumous Exhibitions

1936

At the end of the year, he participated for the first time in a collective exhibition – the II São Paulo Salon of Fine Arts (São Paulo), organized by the State Council for Artistic Orientation. Receives the acquisition prize for the painting "Flight into Egypt," awarded by the commission appointed by the municipal government, chaired by Mrs. Renata Crespi da Silva Prado, wife of the then Mayor of São Paulo, Fabio Prado.

1939

Participates in an exhibition held in São Paulo in honor of Candido Portinari (1903-1962), for the prize won at the International Painting Exhibition (Carnegie Institute of Pittsburgh, United States).

Participates in the 42nd National Salon of Fine Arts (Rio de Janeiro) and the 3rd and 4th São Paulo Salons of Fine Arts (São Paulo), receiving the Grand Silver Medal in all three. At the end of the year, he appears in the "Exhibition of Small Paintings" at the Palácio das Arcadas (São Paulo), where he becomes more intimately acquainted with Rebolo. The exhibition, organized by Torquato Bassi, was supported by the São Paulo Society of Fine Arts (later renamed the Union), and held to raise funds for charity. Sergio Milliet purchased the work "Burying the Dead," which the artist later reacquired and repainted (the sky, now a vibrant color, is the result of the intervention carried out in the 1980s). Piccolo also acquired works by the artist.

It is part of the 1st São Paulo Artistic Family Salon, organized by Paulo Rossi Osir and Vittorio Gobbis, at the Esplanada Hotel (São Paulo). The catalog features an introduction by Paulo Mendes de Almeida. Pennacchi exhibits the paintings "Virgin with Child," "Supper of the Apostles," "Landscape," "Still Life," and "Composition." He also participates in the 5th São Paulo Salon of Fine Arts (São Paulo).

He participated in the II Salon of the Paulista Artistic Family, held in the halls of the Automobile Club, at 287 Líbero Badaró Street. The illustration on the catalog cover is by the artist. He also participated in the III Salon of May, held at the Itá Gallery, where the Annual Magazine of the Salon of May – RASM – was published.

1940

Participated in the III Salon of the Paulista Artistic Family, promoted by the Association of Brazilian Artists and the magazine Aspectos. The group's last collective exhibition took place at the Palace Hotel (Rio de Janeiro).

1941

In October, he participated in the I Art Salon of the National Industry Fair, at Parque da Água Branca (São Paulo), organized by Quirino da Silva, Vittorio Gobbis, and journalist Elias Chaves Neto. Among other works, he presents a Saint Francis, mentioned in an article by Mário de Andrade commenting on the 5th Union Salon.8 The event was discontinued.

1942

In July, he participates in the 7th Union Salon of Visual Artists, at the Prestes Maia Gallery. Since 1936, the São Paulo Society of Fine Arts had transformed itself into the Union of Visual Artists and Musical Composers.

1945

In June, he presents a solo exhibition at the Galería Müller (Buenos Aires, Argentina), where he exhibits 47 paintings, including oils, gouaches, and temperas, on religious and customary themes. The exhibition was organized by Giuseppe Chiappori, with the help of Filomena and her housekeeper, Malanie Van Derkel. The exhibition was publicized by the newspapers La Nación, El Pueblo, La Razón, Correo Literario, and a periodical for the German community: Argentinisches Tageblatt. It is possible that critic Margherita Sarfatti, an important promoter of the Novecento, wrote a review of the exhibition (not found). Pennacchi, however, was unaware of it.

In August, he participated in the "Exhibition of Modern Brazilian-North American Painting" at the Galeria Prestes Maia. The event, originating from Rio de Janeiro, was an initiative of the commercial company Contemporary Arts.

In October, he held a solo exhibition at Galeria Itá, presenting 70 works: 27 with sacred themes, 43 secular, including seven still lifes, four drawings, three tempera paintings, and two small frescoes. Cena Brasileira, considered by critics to be one of his finest works, was acquired by Cicillo Matarazzo and later donated to the future Museum of Contemporary Art at the University of São Paulo.

1946

In February, he joined the collection of the Art Section of the São Paulo Municipal Library, designed by Sergio Milliet, with a drawing.

Participates in the 12th São Paulo Salon of Fine Arts, at the Prestes Maia Gallery.

1949

In March, he participated in the group show "Exposição de Pintura Paulista" (São Paulo Painting Exhibition) at the Ministry of Education and Health (also a sponsor) in Rio de Janeiro, organized by the São Paulo gallery Domus. Also included in the exhibition are works by Aldo Bonadei, Alfredo Volpi, Di Cavalcanti, Flávio de Carvalho, Francisco Rebolo Gonsales, José Antonio da Silva, Lúcia Suaré, Nelson Nóbrega, Noêmia Mourão, Quirino da Silva and Yolanda Mohalyi. Pennacchi presents eight oils and gouaches: Circus, Village, The Witch (reprinted in the catalogue), Balloon, Alms, Annunciation, Visitation and Composition.

He also participates in the 1st Bahian Salon of Fine Arts, held at the Hotel Bahia, Salvador.

1950-1964

Pennacchi opts for self-imposed exile. According to the artist: "because I disagreed with the chaotic development of the visual arts in the 1950s, I decided to return to my world and continue researching and working."11

1951

Participates in the 1st São Paulo Biennial, an exhibition organized by the São Paulo Museum of Modern Art. Pennacchi submitted three works, but only one was chosen for the exhibition: a fresco on plaster titled Figures, from 1950.

1953

He participated in the XVIII São Paulo Salon of Fine Arts, at the Prestes Maia Gallery.

1954

In May, he participated in the III São Paulo Salon of Modern Art, at the Prestes Maia Gallery. He also participated in the group show "Contemporary Art: Exhibition of the Collection of the Museum of Modern Art of São Paulo," at the same museum.

1960

He participated in the group show "Christmas Cards," organized by the Atrium Gallery. Encouraged by Emy Bonfim, he exhibits miniatures with great repercussion in the artistic community.

1964

Solo exhibitions are held at the Azulão Gallery and the Casa do Artista Plástico Art Gallery (São Paulo). At the latter, he exhibits paintings and ceramic pieces.

1966

From that date on, several exhibitions by the Santa Helena Group follow one another. The first of these – "The Santa Helena Group, Today" – takes place at the 4 Planetas Art Gallery. The following year, the Auditório Itália organizes the exhibition "The Santa Helena Group: 30 Years Later."

From that date on, several exhibitions by the Santa Helena Group follow one another. The first of these – "The Santa Helena Group, Today" – takes place at the 4 Planetas Art Gallery. The following year, the Auditório Itália organized the exhibition "The Santa Helena Group: 30 Years Later."

1970

In Estoril, Portugal, he was invited to participate in the group show "Brazilian Ingenuous Artists," held at the Estoril Casino.

1972

Two important exhibitions took place that year: "The Week of 22: Antecedents and Consequences," an initiative by Pietro Maria Bardi, held at the São Paulo Museum of Art Assis Chateaubriand, and "Art/Brazil/Today: 50 Years Later," organized by Roberto Pontual, at the Collectio Gallery.

Later that year, the Galeria Azulão exhibited drawings by the Santa Helena Group: Bonadei, Graciano, Manuel Martins, Rebolo, Rizzotti, Volpi, and Zanini.

1973

In São Paulo, four solo exhibitions were held: in April at the São Paulo Museum of Art; in May at the Circolo Italiano (Edifício Itália); and in November at the Espade Galeria de Arte. In addition, a solo exhibition was held in June in Milan, Italy. The MASP retrospective, an initiative of Pietro Maria Bardi, is undoubtedly the most important, providing a broad understanding of the artist's work. 152 works listed in the printed edition are presented, including paintings, drawings, frescoes, and ceramics (not listed). Eight self-portraits from different periods are on display. The newspapers consider the solo exhibitions to be "the Pennacchi year."

In August, at an auction organized by Galeria Collectio, the artist is honored with a solo exhibition featuring 27 paintings spanning 40 years of artistic activity. Galeria Espade also presents paintings by the artist.

He is part of the Panorama of Current Brazilian Art / Painting, organized by the Museum of Modern Art of São Paulo, which features the works: Casamento (1968), Cafezal (1970), Circo (1972), and Aldeia (1973), reproduced in the catalog. Uirapuru Galeria de Arte presents "Eight Painters of the Santa Helena Group," and Galeria Azulão presents "São Francisco as Seen by the Artists...". In Milan, the Itamaraty (Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs) organizes a collective exhibition of Brazilian artists, of which Pennacchi is a member.

The São Paulo Museum of Art presents five of the artist's drawings in an exhibition of donations from that year.

1974

Four solo exhibitions are held: in March, at the Bonfiglioli Gallery (São Paulo); a retrospective at the Fundação Cultural do Distrito Federal (Brasília), where 129 works are presented, covering the period from 1929 to 1974; at the Oscar Seraphico Gallery (Brasília), under the sponsorship of the Italian Embassy and the support of Yvone Giglioli – Italian Ambassador to Brazil –; and an exhibition of mini-paintings at the Guimar Gallery (São Paulo).

1975

Presents ceramic panels with folkloric themes, in collaboration with Eunice Pessoa, at the Clube Athletico Paulistano (São Paulo). Pennacchi met the ceramist at one of her exhibitions and accepted her suggestion to collaborate. This exhibition is the duo's first.

The Emy Bonfim Gallery is exhibiting 30 paintings by Pennacchi and ten ceramic panels by the Pennacchi-Eunice Pessoa duo.

In March, the Paço das Artes and the Museum of Image and Sound are organizing a joint exhibition about Pennacchi and the Santa Helena Group: "Pennacchi and Some Artists of the Santa Helena Group" (Paço) and "Other Painters of the Group" (MIS). The exhibition includes works by Aldo Bonadei, Alfredo Rizzotti, Alfredo Volpi, Clóvis Graciano, Francisco Rebolo Gonsales, Humberto Rosa, Manoel Martins, and Mario Zanini. Pennacchi presents 12 works dated from 1936 to 1950.

In September, the Santa Helenistas will host a commemorative exhibition celebrating the group's 40th anniversary, also featured at the Palácio das Artes (Galeria Genesco) in Belo Horizonte. Curated by Aurora Duarte and Fábio Porchat, works by Bonadei, Graciano, Rebolo, and Volpi, in addition to Pennacchi, will be presented.

1976

The artist donates 133 drawings to MAC/USP, including studies for murals in the chapel of the Hospital das Clínicas, the Chapel of the Church of Saint Peter and Saint Paul, the Auxiliary Bank of São Paulo, and the Catholic Ladies' League, among others.

The Emy Bonfim Gallery presents a solo exhibition by the artist.

He once again participates in the Panorama of Contemporary Brazilian Art / Painting, at the Museum of Modern Art of São Paulo, with the works: Annunciation (1975), Village with Balloons (1976), and Bread (1976), reproduced in the catalog.

In June, the Lasar Segall Museum presents "The Salons: of the Paulista Artistic Family, of May, and of the São Paulo Visual Artists' Union," an exhibition organized by Lisbeth Rebollo Gonçalves.

1977

He presents a solo exhibition at the Brazil-United States Cultural Center Gallery (Santos), in an exhibition of paintings (from the 1960s and 1970s), drawings, frescos, and ceramics, in the inaugural exhibition of the Entreartes Gallery, and at the Friends of the Arts Club Gallery (São Paulo). Paulo).

At the Brazilian Art Museum of the Armando Álvares Penteado Foundation (São Paulo), the exhibition "Seibi Group – Santa Helena Group: 1935s and 1945s" is organized.

1978

Part of the 3rd Noroeste Visual Arts Salon, at the Penápolis Educational Foundation (School of Philosophy, Sciences, and Letters). The Academus Decorações Art Gallery (São Paulo) organizes the group show "Small Canvases – Great Painters," of which the artist is a member.

1979

In celebration of 50 years of artistic activity in Brazil, the Paulo Figueiredo Art Gallery (São Paulo) hosts the first exhibition to emphasize drawing. In June, the Oscar Seraphico Gallery (Brasília) also pays tribute to the artist, presenting paintings, drawings, and prints.

The Uirapuru Art Gallery (São Paulo) presents an exhibition on the Santa Helena Group.

1980

Three solo exhibitions are held: at the Academus Decorações Art Gallery, presenting 30 paintings (São Paulo), at the Samson Flexor Gallery (Marília), and at the Kattya Art Gallery (Salvador).

That year, in 1982 and 1985, he again participates in the Noroeste Visual Arts Salon (IV, V, and VI) at the Penápolis Educational Foundation. He also participates in the group show "Landscape Painters" at the André Art Gallery (São Paulo).

1981

Drawings and studies are presented at the Gerot Gallery (São Paulo).

1982

The artist's solo exhibition marks the inauguration of the new headquarters of the André Gallery (São Paulo).

In June, the São Paulo Museum of Modern Art holds the exhibition "From Modernism to the Biennial."

1984

The André Art Gallery (São Paulo) pays tribute to the artist in the exhibition "Pennacchi – sixty years of painting." Two other solo exhibitions are held at the Ars, Artis Gallery (São Paulo), featuring studies, drawings, and mixed-media works, and at the Academus Gallery in Curitiba.

His works are presented in the group show "Tradition and Rupture: Synthesis of Brazilian Art and Culture" at the São Paulo Biennial Foundation.

1985

In celebration of the artist's 80th birthday, three solo exhibitions are presented: at the Academus Decorações Art Gallery (São Paulo), the Grossman Gallery (São Paulo), and the Convention Hall of the Hotel Bologna in Campos do Jordão.

He is part of the VIII National Salon of Visual Arts at the Museum of Modern Art in Rio de Janeiro. The São Paulo Museum of Art presents 100 works from the Itaú collection, and the Ranulpho Gallery (São Paulo) presents the exhibition "Mothers and Flowers in the View of 33 Painters."

1986

In his hometown, at the Sala Ex-Archivio Provinciale (Castelnuovo di Garfagnana, Lucca, Italy), an exhibition is held featuring 40 works from the collections of the parishes of Villa Collemandina and Castiglione, as well as the private collections of Giovanni Giannotti, Nello Pennacchi dei Capitani, Nicolau Pennacchi dei Cannari, and Luigi Suffredini. The exhibition is curated by Guglielmo Lera and Nicolau Pennacchi.

Two other important solo exhibitions are held. The first marked the opening of the art gallery of the State Bank of Minas Gerais (São Paulo), and another at the Jardim Contemporâneo Gallery, an initiative of the Ribeirão Preto Department of Culture, where he was welcomed as an official guest of the city. That same year, he presented oil paintings, drawings, and mixed-media works in the convention hall of the Savoy Hotel in Campos do Jordão.

In São Paulo, he participated in the group shows "Artists and Football" at the Grossman Gallery and "Time of Maturity" at the Ranulpho Art Gallery.

That year and the following three, he participated in a group show organized by Sociarte. The first three editions were presented at the Monte Líbano Athletic Club (São Paulo), and the last at the Ripasa headquarters in Americana.

1987

The artist presented a solo show at the André Art Gallery (São Paulo).

He is honored as patron of the 6th Art Salon, organized by São Judas College (São Paulo), where he receives the "Highlight of the Year" and "Merit of Honor" trophies.

He participates in the Christmas group show at the André Art Gallery (São Paulo) and "Six Figuratives" at the Banco do Estado de Minas Gerais Gallery (São Paulo).

He participates in the "Contemporary Art Exhibition," held at the Chapel Art Show at Maria Imaculada College (São Paulo). He will also be featured in the 1988 and 1989 editions.

1988

In Curitiba, the artist is honored with a solo exhibition at the Simões de Assis Art Gallery in June.

MAC/USP organizes the exhibition "MAC 25 Years: Highlights from the Initial Collection," in which the artist participates with the work Cena Brasileira. Ranulpho (São Paulo) also holds the group show "O Circo." The following year, the same gallery presents "Thirty-Three Ways of Seeing the World."

1989

The artist's last solo exhibition during his lifetime is held at Galeria Jacques Ardies (São Paulo). At the end of the year, the same gallery hosted the launch of the book "Ofício de Pennacchi" (Gema Design Editora).

1990

He was honored at the 14th Cultural Exhibition of Immigrants and the 1st Immigration and Integration Arts Salon in São Paulo.

His works were featured in an exhibition by the São Paulo Association of Art Critics at the São Paulo Jockey Club, in addition to the group show, in September, of the exhibition "Tribute to Israel," organized by the Friends of Israel Association and the Grossman Gallery (São Paulo). Pennacchi donates some works to the charity.

1991

Presented works by the artist, created between 1928 and 1982, are presented at the Ars Gallery, Artis (São Paulo).

1992

He dies on October 5th, after a long illness. He is buried in the Consolação Cemetery (São Paulo), in the Matarazzo and Matarazzo-Pennacchi family plot.

The Mário de Andrade Municipal Library is holding the important exhibition "Sérgio's Perspective on Brazilian Art: Drawings and Paintings," featuring works from the collection of historian Sérgio Buarque de Hollanda.

In December, he receives a tribute at the Christmas auction held by Aloísio Cravo (São Paulo).

1993

Since that year, his work has been featured in several posthumous events, beginning with the II Exhibition of Italian-Brazilian Artists at the Fiat Cultural Space (São Paulo), sponsored by Fiat Brazil and supported by the Italian Consulate and the Italian Institute of Culture and the Italian-Brazilian Institute.

1994

Preceding the 22nd São Paulo International Biennial, the Biennial Foundation organizes the historic exhibition "Brazil Biennial 20th Century," under the general curatorship of Nelson Aguilar.

Grossman Gallery in São Paulo presents the exhibition "Dentists and Football."

1995

The São Paulo Museum of Modern Art holds an exhibition on the Santa Helena Group, curated by Walter Zanini, presented the following year at the Banco do Brasil Cultural Center (Rio de Janeiro).

1996

The artist's works from the MAC/USP collection are presented in the exhibition "Brazilian Art: 50 Years of History in the MAC/USP Collection: 1920-1970."

1997

"Great Names" The "Brazilian Painting" exhibition (Jô Slaviero Gallery) and the Christmas group show at the André Art Gallery, both in São Paulo, feature works by Pennacchi.

1998

That year, the artist's mother-in-law – Countess Adele Dall'Aste Bradolini in Matarazzo – passed away and was buried in the Consolação Cemetery (São Paulo). Hours after the burial, the tomb, which had been decorated with a ceramic angel by the artist since the 1970s, was vandalized during a black mass ritual.

The André Art Gallery organized the Spring group show, and "Impressions: The Art of Brazilian Engraving" took place at the Banespa Cultural Space (São Paulo).

1999

In São Paulo, two solo exhibitions were held: at the Clube Atlético Paulistano and at the Ars, Artis Gallery. At the Jô Slaviero Art Gallery, also in São Paulo, he organizes a group show of drawings and watercolors.

2000

The Museum of Brazilian Art (Armando Álvares Penteado College, São Paulo) organizes the important retrospective "Unveiling Pennacchi," curated by Fábio Porchat. The exhibition presents the artist's little-known work, primarily from the family collection.

Three group shows take place that year in São Paulo: "Naive Art" at the Jacques Ardies Gallery (a second edition follows in 2002), "The Human Figure in the Itaú Collection" at Itaú Cultural, and "Santa Helena Group" at the Jô Slaviero Art Gallery.

2001

The artist's work is featured in two exhibitions: the first, in Rio de Janeiro – "Brazilian Watercolor" – at the Light Cultural Center; the second, in São Paulo – "Figures and Faces" at A Galeria.

2002

The book Pennacchi – Mural Painting, with text by Valerio Antonio Pennacchi (Metalivros), is published in commemoration of the tenth anniversary of the artist's death.

Dan Galeria (São Paulo) organizes a commemorative exhibition of the artist, curated by Valerio Antonio Pennacchi. His work is featured in three other group shows in São Paulo: "Modernism: from the Week of '22 to the Sergio Milliet Art Section" (São Paulo Cultural Center), "Workers on Paulista Avenue: MAC-USP and the Artisan Artists" (Sesi Art Gallery), and "Santa Ingenuidade" (Unifieo College).

2003

The important exhibition "Novecento Sudamericano," curated by Tadeu Chiarelli, is shown at the Palazzo Reale in Milan (Italy) in March and at the Pinacoteca do Estado (São Paulo) in August of the same year.

In July, his work is presented in the group show "Olhares sobre Campos do Jordão" (Views of Campos do Jordão) at the Hotel Toriba in that city.

In December, the exhibition "Two Interpretations of Brazilian Art" features works by the artist and his son Lucas, curated by Valerio Antonio. Pennacchi.

2004

The frescoes of the Hotel Toriba, in Campos do Jordão, are the subject of the lecture series, organized by Flávia Rudge Ramos, "Landscape in Painting and the Restoration of Pennacchi's Frescoes," during a workshop with speakers Flávia Rudge Ramos, Julio Moraes, Elza Ajzenberg, and Valerio Antonio Pennacchi.

2005

In São Paulo, in celebration of the 70th anniversary of the Santa Helena Group, two exhibitions are taking place: at the Vivo and BM&F Cultural Centers, the first curated by Lisbeth Rebollo Gonçalves; the second, by Luzia Portinari Greggio.

The Moreira Salles Institute (São Paulo) presents a little-known work by the artist in the exhibition "The 'Advertisements' of Fulvio Pennacchi: Beginnings of Brazilian Advertising," showcasing 58 advertising poster projects created in the 1920s and 1930s, currently part of the institution's collection. The exhibition is scheduled for other Institute locations (Rio de Janeiro, Belo Horizonte, Poços de Caldas, Porto Alegre, and Curitiba).

In November, in Campos do Jordão, the "1st Annual Visual Arts Meeting" will be held, organized by the NGO "Ame Campos." Among the lectures, two are dedicated to the artist's work: "Pennacchi the Muralist," by Valerio Antonio Pennacchi, and "Pennacchi and Mural Painting in Brazil," given by José Roberto Teixeira Leite.

5. Bibliography, Awards and Honors

Specific Books

BARDI, Pietro Maria. Pennacchi. São Paulo: Raízes Artes Gráficas, 1980.

PENNACCHI, Valerio Antonio. Pennacchi's Craft. São Paulo: Gema Design Editora, 1989.

________. Pennacchi: Mural Painting. São Paulo: Metalivros, 2002.

________. Pennacchi: Forty Years. São Paulo: Novo Mundo Art Center, 1973.

________. Pennacchi: Forty Years; Album with poems and reproductions. São Paulo: Massao Ohno Editora, 1973.

Encyclopedias, dictionaries, and books from public collections

AMARAL, Aracy. Profile of a collection. São Paulo: Museum of Contemporary Art, 1988. AYALA, Walmir. Dictionary of Brazilian Painters. Rio de Janeiro: Spala, 1986. CAVALCANTI, Carlos. Brazilian Dictionary of Visual Artists. Brasília: National Book Institute; Ministry of Education and Culture, 1977-80. (3rd vol., 1977) BARDI, Pietro Maria. 100 Works of Itaú. São Paulo: Banco Itaú, 1985. ________. São Paulo Museum of Art Assis Chateaubriand. São Paulo: Melhoramentos, 1985. BARROS, Stella Teixeira de. Profile of the Itaú Collection. São Paulo: Itaú Cultural, 1998. LEITE, José Roberto Teixeira. Critical Dictionary of Painting in Brazil. Rio de Janeiro: Artlivre, 1988. OUR CENTURY. São Paulo: Abril Cultural, 1980. (vol. 1930/1945 – The Vargas Era) PONTUAL, Roberto. Dictionary of Visual Arts in Brazil. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 1969. ZANINI, Walter (org.). MAC – General Catalog of Works. São Paulo: Museum of Contemporary Art, 1973.

Citation in books

ALMEIDA, Paulo Mendes de. From Anita to the Museum. 2nd ed. São Paulo: Perspectiva, 1976.

________. Santa Helena Group: Engravings. São Paulo: Collectio Artes, 1971.

AMARAL, Aracy. Art and the Artistic Medium: Between Feijoada and Cheeseburger (1961-1981). São Paulo: Nobel Prize, 1983.

ANDRADE, Mário de. José Roberto Teixeira Leite (org.). Essays on Clovis Graciano. São Paulo: Marco Antônio Marcondes and Maria Fittipaldi Publishers, 1975.

ARAÚJO, Olívio Tavares de. The Loving Look. São Paulo: Momesso Art Editions, 2002.

ARROYO, Leonardo. Churches of São Paulo. Rio de Janeiro: José Olympio, 1954.

BARDI, Pietro Maria. The Week of 1922: Antecedents and Consequences. São Paulo: Museum of Art of São Paulo, 1972.

________. Profile of the New Brazilian Art. Rio de Janeiro: Kosmos, 1970.

BRAGA, Teodoro. Artist Painters in Brazil. São Paulo: São Paulo Editora, 1942.

BRILL, Alice. Mario Zanini and his Time. São Paulo: Perspectiva, 1984.

BRITO, Mário da Silva. History of Brazilian Modernism. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 1978.

BUENO, Odair; Patrocínio, Ivo. Balloon, Inexplicable Passion. São Paulo: Sonora, 1999.

CANAMI, Olympia Parenti. Lucca, dei Mercati-Patrizi Lucchesi. Florence: Nardini Editore, 1977.

CENNI, Franco. Italians in Brazil. São Paulo, Martins Editora, n.d.

CHIARELLI, Tadeu. Brazilian International Art. 2nd ed. São Paulo, Lemos Editorial, 2002.

CIVITA, Victor (ed.). Art in Brazil. São Paulo: Nova Cultura, 1986.

DEBENEDETTI, Emma; SALMONI, Anita. Italian Architecture in São Paulo. São Paulo: Perspectiva, 1981.

GONÇALVES, Lisbeth Rebollo. 40 Years: Santa Helena Group. São Paulo: Government of the State of São Paulo, 1975.

________. Aldo Bonadei. The Journey of a Painter. São Paulo: Edusp, 1990.

________. Sergio Milliet, Art Critic. São Paulo: Edusp, 1992.

KAWALL, Luiz Ernesto Machado. Arts – Reporting. São Paulo: New World Arts Center, 1972.

LAUAND, Luis Jean. Philosophy, Education and Art. São Paulo: IAMC Editions, 1988.

LEITE, José Roberto Teixeira. Modern Brazilian Painting. Rio de Janeiro: Record, 1978.

LOURENÇO, Maria Cecília França. Workers of Modernity. São Paulo: Hucitec; Edusp, 1995. (Urban Studies, series “Art and Urban Life 3)

MAMMÌ, Lorenzo. Volpi. São Paulo: Cosac & Naify, 1999.

MANSELLI, Raoul. The Republic of Lucca. Turin: Utec Libreria, 1986.

MILLIET, Sergio. Critical Diary. São Paulo: Department of Culture, 1950. (vol. 6)

________. Painters and Paintings. São Paulo: Martins Editora, 1940.

PEIXOTO, Mário dos Santos. Brazilian Art – 20th Century. Rio de Janeiro: National Museum of Fine Arts, 1984.

PENNACCHI, Nicola. La Garfagnana and its History. Lucca: The Province of Lucca, 1977.

PONTUAL, Roberto. Art Today – Brazil: 50 Years Later. São Paulo: Collectio Artes, 1973.

REBOLO. São Paulo: Best Editora, 1987. (MWM Collection)

SALZSTEIN, Sônia. Volpi. Rio de Janeiro: Silvia Rossler Editora; Campos Gerais, 2000.

SARFATTI, Margarita G. Mirror of Contemporary Painting. Buenos Aires: Argos Editorial, 1947.

TRENTO, Ângelo. The Italians in Brazil / Gli Italiani in Brasile. São Paulo: Melhoramentos, 2000.

WEBSTER, Maria Helena. The Metropolis. São Paulo: Celia de Assis Publishing; Lobello Marino Publishers.

ZANINI, Walter. Art in Brazil in the 1930s-40s: The Santa Helena Group. São Paulo: Nobel; Edusp, 1991.

________. (coord.). General History of Art in Brazil. São Paulo: Walther Moreira Salles Institute; Djalma Guimarães Foundation, 1983. (vol. II)

Periodicals

Magazines

ANDRADE, Mário de. Essays on Clóvis Graciano. In MOTTA, Flávio. “The Paulista Artistic Family”, Journal of the Institute of Brazilian Studies – IEB, Appendix II (offprint), São Paulo, No. 10, 1971.

CHIARELLI, Tadeu. “The Novecento and Brazilian Art”. Journal of Italian Studies, São Paulo, FFLCH/USP, 3:3, July 1993. (Republished in Chiarelli, Tadeu. Brazilian International Art)

KRÜSE, Olney. “Fulvio Pennacchi: An Italian Painting Brazil”, Gallery, São Paulo, May 1987.

LERA, Guiglielmo. “Religiositá di Fulvio Pennacchi”, Revista dell’Istituto Storico Lucchese, Lucca, 1984.

MILINI, Father Francesco (C.S.). “La chiesa della pace, l’imigrato italiana”, Piancenza, 1984.

OCEAN, Rassegna. Mensile di Cultura, Buenos Aires, nº 11, anno III, jul. 1945.

PENNACCHI, Nicola. “Fulvio Pennacchi: a Garfagnino artist who celebrates all of Italy”, La Garfagnana. Castelnuovo di Garfagnana, Garfagnana (Lucca), gennaio 1970.

PENNACCHI, Nicola. “Garfagnini che si farmo onore all’estero: Fulvio Pennacchi”, La Garfagnana. Castelnuovo di Garfagnana, Garfagnana (Lucca), July 1973.

PENNACCHI, Nicola. “References to a Garfagnana painter in Brazil”, La Garfagnana. Castelnuovo di Garfagnana, Garfagnana (Lucca), July 1973.

ANNUAL REPORTS of the Banco de Crédito Real de Minas Gerais S.A., Juiz de Fora, 1973/1974.

ANNUAL MAGAZINE of the May Salon, São Paulo, No. 1, 1939.

RIMONDI, Fr. Mario. Messenger of Peace. Monthly Organ of the Pious Society of the Missionaries of Saint Charles Borromeo. São Paulo: Editions from 1939 to 1946 and special edition of December 1950.

SEAVONE, Miriam. "The Art of Longing, Surprises of Bronze and Marble," Veja, November 10, 1996.

SOUZA, Ana Paula. "Enclave of Beauty," Carta Capital, No. 388, Year XII, April 12, 2006.

WAHL, Jorge. "Profits from Art," Senhor Magazine, São Paulo, No. 66, June 26, 1982.

Newspapers

“Pennacchi’s Fresco Threatened with Destruction,” The State of São Paulo, São Paulo, April 27, 1982.

ALMEIDA, Paulo Mendes de. “Sé Square, No. 231,” Folha de S.Paulo, São Paulo, March 9, 1975.

ANGIOLILLO, Francesca. “‘Fate’ Returns Fresco by Fulvio Pennacchi to the Family,” Folha de S.Paulo, São Paulo, May 28, 2002.

BARDI, Pietro Maria. “Italian Pittori in Brazil,” Fanfulla, São Paulo, June 13, 1954.

BARROS, Âmbar de. “Pennacchi Frescoes Preserved,” Folha da Tarde, São Paulo, December 10, 1984.

________. “Engineering saves these works of art”, Jornal da Tarde, São Paulo, 12 December. 1984.

________. “Pennacchi fresco saved from demolition”, Folha da Tarde, São Paulo, 10 December. 1984.

“BELLAS Artes”, La Nación, Buenos Aires, 18 June 1945.

“BILDENDE KUNST”, Argentinisches Tageblatt, Buenos Aires, 19 June. 1945.

CATTANI, Roberto. “La belleza dell’umiltá – Gli 80 anni di Fulvio Pennacchi”, Il Corriere, São Paulo, 27 Jan. 1986.

CENNI, Franco. “Profili d’artista: Fulvio Pennacchi”, Fanfulla, São Paulo, 1936.

________. “A Modern Painter”, Fanfulla, São Paulo, July 17, 1936.