Arthur Piza

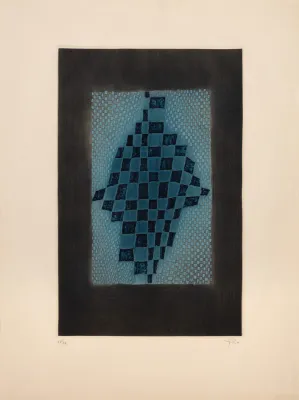

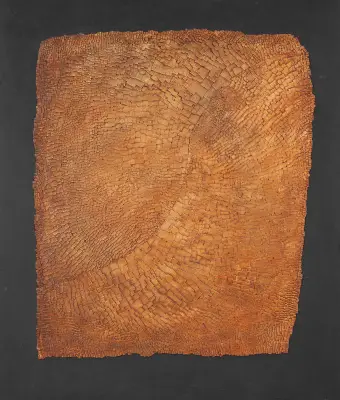

Untitled

collage of clippings on paper28 x 21 cm

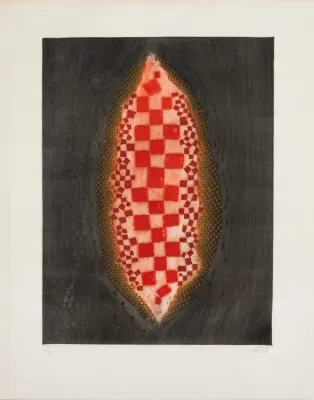

Untitled

clipped paper collage1962

97 x 80 cm

reproduced in the book "Arthur Luiz Piza". São Paulo: Cosac & Naify, 2002. p.74 and 75.

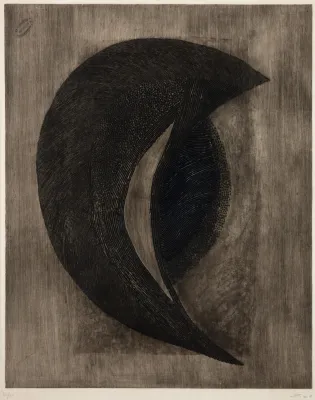

Untitled

clipped paper collage24 x 20 cm

Arthur Piza (São Paulo, SP, 1928 - Paris, 2017)

Arthur Piza was an engraver, draftsman, and sculptor. He began his artistic training in 1943, studying painting and fresco with Antonio Gomide (1895-1967). After participating in the 1st São Paulo International Biennial in 1951, he traveled to Europe, settling in Paris. There, he frequented the studio of Johnny Friedlaender (1912-1992), where he perfected his metal engraving techniques, including etching, intaglio, aquatint, and drypoint.

In 1953, he participated in the 2nd São Paulo International Biennial, where he was awarded the acquisition prize. At the 5th Biennial in 1959, he received the grand national prize for engraving. During this period, he began experimenting with reliefs, chopping up his watercolors and using the fragments for collages on canvas, paper, copper, and wood.

Later, he created metal reliefs on sisal and produced large-scale three-dimensional works, as well as porcelain and goldsmithing. He also illustrated several limited-edition books. In the late 1980s, he created a three-dimensional mural for the French Cultural Center in Damascus, Syria. In 2002, two major retrospectives of his work were presented at the Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo (PESP) and the Museu de Arte do Rio Grande do Sul Ado Malagoli (MARGS) in Porto Alegre.

Critical Commentary

Arthur Luiz Piza took a painting and fresco course with Antonio Gomide (1895-1967) in 1943. In 1951, he studied in Paris with Johnny Friedlaender (1912-1992) and perfected his metal engraving techniques. His first engravings echo Friedlaender's through their irregular graphics and surrealist nuances.

Gradually, his works developed a greater concern for constructiveness, with the geometrization of elements. Piza introduced a new way of working into engraving: he began to sculpt geometric shapes—rounded, rectangular, or triangular—into the metal plate using a burin, various gouges, a nail, and a hammer. The resulting engravings explore the transition between areas of varying depth and the interplay created with light.

Piza then realized that this process could be translated into painting. In 1959, he began creating reliefs by chopping up some watercolors he had made at the time and using the small fragments to create collages on paper or canvas, like mosaics, which were sometimes covered with layers of paint. According to the artist, the material is organized based on the search for the rhythm of each composition, independent of the others already completed.

As scholar Stella Teixeira de Barros points out, color becomes increasingly insinuated in his work, as does the rhythm of the particles in relief. The forms tend to cluster together in more saturated patterns. For critic Paulo Sérgio Duarte, these reliefs contain a desire for order that is not realized. Although they contain something reminiscent of serialization and repetition, the small, subtly irregular particles combine and coexist with directional freedom, sometimes almost chaotic.

In the Doormats series, 1979, the artist's tendency to occupy space becomes more visible. The works are composed of triangles attached to metal pins on pieces of sisal. As critic Tiago Mesquita points out, in these works, what previously suggested volume and flow transforms into three-dimensionality. In 1986, Piza created a mural for the French Cultural Center in Damascus, with a poetic approach similar to that presented in the works in this series.

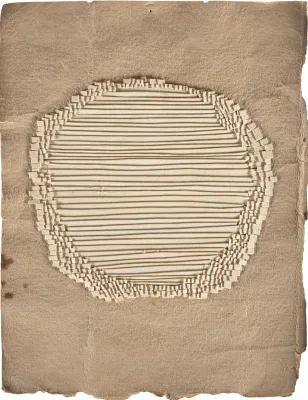

The "Cut and Cut" series, 1984/1985, is created using deep incisions in sheets of paper. In some of these works, color enhances the perception of volume. In others, as Barros points out, preserving the white of the paper allows the work to reach the pinnacle of modulated and changing luminosity. The artist's gestures can still be seen in the material, in a process similar to engraving.

Piza also develops experiments with wood carving, designing utensils such as plates, vases, and porcelain objects, and creates chiseled metal objects and jewelry.

Critiques

"He who sculpts marble and engraves the heart, but who also imprints signs, is, in Latin, a 'Piza sculptsit.' We know, of course, his engraved work, but forget that he worked the material, and it is good to rediscover his sculptures to better understand the process, the same closed but fluid writing, firm and soft like the dawn on clear reliefs still dormant.

Does Piza know where he is going? He only needs to carve the signs to defy time, to work indefinitely with a precise chisel, to wound the bark, to animate the skin of things so that the long work of the abysses finally emerges on the surface of the earth. Like the Akkadian tablets, like a new Braille alphabet, so many messages whose meaning escapes the artist; however, more than the code, what matters is the writing itself, this extremely limited play of signs and sets constantly revisited, to the point of obsession, without implying repetition or monotony. What matters is the tactile simplicity of the style, the rigor of a poetry meant to be touched, austere music of shadow and light. Thus Piza traverses the space of the dream and carves it with his constellations. He aligns its white slopes for the assembly of the clairvoyants."

François Mathey

MATHEY, François. In: PIZA. Arthur Luiz Piza. São Paulo: Gabinete de Arte Raquel Arnaud Babenco, 1983. n. p.

"It is not (...) the field of representation that interests Piza; he only affirms what he shows, refusing to give meaning to his work. It offers itself to the eye as an experience of the work, which is composed by the artist's making."

Although he does not establish in advance, in detail, the successive stages of his work, gratuitousness and inconsequence have no place. Making a small relief, depositing a mark, does not consist of imposing a form on the support, but simply affixing to the support the form expressed by the instrument that affixed it. Repeating a form, a relief, is not recopying it, but making another, within the same gesture, which differs, which determines a unique space, defining reliefs and intervals, shadows and lights, tones and rhythms. Everything happens as if it were a question of freeing the work from its expressive obligations, of letting it unfold within itself. By escaping the lyrical abstractionist trend, when While maintaining a possible connection with the work of Kandinsky and Miró, the artist opted for a constructivist approach, yet one very peculiar, very much his own, due to the strong baroque intonation that carries within its concise and simple simplicity. The search for new rhythms, the exploration of spectra of luminosity lead him to encounter a language permeated by the simultaneous contrast of two planes, by the exaltation of the ranges of relief, by the agonizing chiaroscuro of colors and shadows. The baroque is not found in the meticulous construction of each detail; it emerges as essence, in the expressive and visceral substance of the carving, in the violent and harsh hammering of the bodywork, in the exuberant and resplendent lust that emanates from the reliefs, in the variety of carvings that at every moment complete the organization of the work, in the intonation of the forms that, so vibrant, questions the geometric principle of their initial constitution, transforming visual signs into celebrations of sensuality.

Stella Teixeira de Barros

BARROS, Stella Teixeira de. Constructive/Inverse Baroque Universe. In: PIZA, Arthur Luiz. Arthur Luiz Piza. São Paulo: MAM; Poços de Caldas: Moreira Salles Institute; Curitiba: Cultural Foundation of Curitiba, 1994. p. 14.

"Regarding the edition, Arthur Luiz Piza (...) values the printer's contribution to the production of the engraving, musically allegorized by him as an interpreter of his score; it is no coincidence that Piza recalls his Parisian printer. Having studied in the 1950s with Johnny Friedlaender in Paris, Piza researches hollow forms, not grooves, which, subjected to the pressure of the press, produce reliefs on the paper. With hammers and chisels of different points, he excavates rounded, triangular, and rectangular shapes of varying depths, making his plates the inverse of relief. Piza's compositions highlight transitions between zones of different depths, which interpenetrate over relatively large areas, creating passages that are locally almost imperceptible. These quasi-forms, because they are open and often geometric, play with light, emphasized or diminished in correlation with the incident external light. This is what makes the passage possible. to the reliefs themselves, which Piza does using pieces of cardboard, cut metals, etc., tending his graphic procedures to space."

Leon Kossovitch and Mayra Laudanna

ENGRAVING: Brazilian art of the 20th century. São Paulo: Itaú Cultural: Cosac & Naify, 2000. p.19.

Testimonials

"I change the way I work. I am now forced to face what I do with determination. I cut, and with the cut comes reflection, the need for a new cut. I direct my hand one way, then the other. Sometimes I continue, and as I continue, the curve appears. Sometimes small shapes repeat themselves, obsessive and rhythmic, like the beating of a drum. There are microrhythms that seek to capture what the material contains of tactile and vibrant. There are macrorhythms that are the great cuts. Between them, a back and forth. There are also the cut shapes rising, the seeing through, the seeing the other side. Then I paint the cut surface. Over and over. I like this repetition that recalls, albeit in an opposite way, the old wall that peels and reveals the consecutive layers of old paint. My opposite is painting and repainting toward the future".

Piza

Paris, January 1986

PIZA. Arthur Luiz Piza. São Paulo: Gabinete de Arte Raquel Arnaud, 1986. n.p.

"Piza has his trademark. However, a tireless researcher and self-proclaimed intimacy enthusiast, he always surprises every time he returns to Brazil for new exhibitions. (...) Economical in his forms, simple in his compositions, the artist continues to move and intrigue. Seeing his works is like listening to Beethoven's sonatas: there, indelible, is the trait that identifies him as unique—and therefore easily recognizable. But in each composition there is also something new, that unusual microworld with its own authenticity. (...) To establish this aesthetic particularity, Piza has always given more weight to intuition than to any theory. When he sets to work, for example, he never starts from a preparatory drawing; at most, he claims to have a vague idea of the outline. (...) Friedlaender not only provided him with new knowledge in engraving, but also gave him a sense of Europe. (...) Between the two—disciple and master—a kind of productive relationship was also established. complicity. 'While I admired Friedlaender's knowledge and discipline, he appreciated my researcher side,' recalls Piza. 'I remember breaking a press while doing a new experiment, and he didn't complain; on the contrary, he was thrilled with the end result. Since he seemed exotic to me, I suppose I was to him too. So there was a very interesting exchange.' (...) Early in his career, Piza employed the same elements used by most engravers (...), but soon found his own technique, replacing the gouge with the chisel and mallet. Not a sculptor, Piza began to carve metal plates, carving them with his geometric figures (...). This way, he outlined his interest in relief 'which represents life, nature, as if something were being born, coming out and exposing my interior,' he explains. From this perspective, Piza rejects any hierarchy between engraving and relief. 'Both have the same importance for me,' he assures. But today the artist takes certain Concerns about the public. While he previously exhibited engravings and reliefs together, he now prefers to hold independent exhibitions. This way, he avoids confusion, including for his own pocket. According to Piza, people looked at the affordable prices of the engravings and, despite liking the reliefs, kept them. 'The solution was to separate them, so as not to suffer economic or aesthetic losses,' he concludes. For the committed artisan who likes to do everything himself when it comes to reliefs, his stance is quite different when it comes to engraving. Piza recognizes and respects the work of the printer. (...) 'It may even be demagogic of me, but I make a matrix like a composer writes a score. So the printer acts like the instrumentalist, interpreting and executing the work. Of course, my printer doesn't admit that there's something of his own in my engraving, but that's not true. There is, and I think it's very good that there's this commitment between engraver and printer.' What Piza really doesn't accept is the equivalence between reproduction and multiple. 'Engraving is not like a copy of "record," he states categorically. "Each copy is an original. But since in the early 19th century—when photography didn't yet exist—many reproductions of paintings were made using lithographic matrices, and some pig-headed person like Salvador Dalí always appeared, making hundreds of prints on different papers, just to make money, art suffered," he explains.

Arthur Luiz Piza to Ana Maria Ciccacio

1988

Ciccacio, Ana Maria. Piza exudes stillness and proposes reflection. Engraving and Engravers, São Paulo, year 1, no. 7, 1988. p. 4-6. In: ENGRAVING: Brazilian art of the 20th century. São Paulo: Itaú Cultural: Cosac & Naify, 2000. p. 122.

The Tribulations of the Particle

The work of Arthur Piza, intimate and understated, has, over more than forty years, consistently demanded attention in a manner opposite to what today’s visual processes impose on everyone without exception. The world increasingly presents itself on a panoramic scale, while the artist’s work calmly insists on an almost microscopic apprehension, yet never detached from contemporary currents. This is what we have observed recently. Modern poetics, which is Piza’s, demands a conviction that cannot be abandoned overnight and, for him, this is uniquely expressed in the dynamics of relief, which he has explored systematically. A seemingly simple problem, yet one Piza demonstrates to be inexhaustible—just like life itself, which, when observed under a microscope, is equally inexhaustible and unpredictable, though scientists may seek certain constants. So too with Piza.

The dynamics of relief originate with the detachment of the first particle. This initial emergence carries something of matter awakening from stillness—the moment when an autonomous unit confronts the indistinct uniformity of the plane. An “I” arises. Free, mobile, uncertain, it establishes the opposition between the static whole and the dynamic unit. While this brings him close to kinetic art, historically and processually, a distinction must be made: the movement in his work is slow, gradual, cumulative—it unfolds in time, not space. Were we to convert each work into a frame, we would have a perfectly structured cinematic sequence narrating the tribulations of the particle, beginning with resistance to movement and evolving into full mobility in his current works: the Bildungsroman of Piza’s particle.

Within this internal dynamic of relief, on the scale of intimacy and proximity in which it exists, I believe one can find a parallel between the tensions of two great artists: Fontana and Calder. Fontana’s rupture of the plane and Calder’s complete freedom of particles. At the intermediate point of these tensions lies the space of Piza’s relief. Here, the particles do not fully liberate themselves, nor do they move like Calder’s; they take a first step and, much like Fontana’s cut, repeat it—yet differently.

Initially, the plane is indistinguishable from matter. They blend together. It is not a purely abstract plane; it evokes not just any matter, but primordial matter—the matter as fundamental to matter as the plane is to abstraction. Arid, dry, hard, an undefined crust, land still barren, prior to life. Thus, the first fracture of the plane is not abstract but organic. It begins with a craquelé, a few tiny fissures, mere cracks emerging as if from fossilized, slow, almost inert time: the discreet eruption of the surface, the first slow and difficult rupture of planar tension. Simultaneously, this fissure establishes the break with the plane while defining the first dimension and behavior of the particles. None initially escape a primitive, gregarious, group behavior, examples of prehistoric regularity. The moment of individuation is still distant. Each particle is part of the whole, which provides cohesion and structure. When the particles move, their direction and trajectory are determined by the ensemble. There is no wandering or autonomy. Planar tension still dominates the individualities, and their natural movement is harmonious. Initially, not even color distinguishes them—they share the same earthy tones as the plane, a trace of a microgeological or cellular primitive phenomenon.

It is likely that Piza has explored every possible behavior of this small element within its intimate and fragile space. From the cohesive ensemble of particles to the pinched and cut surface element, from units defined by square metal plates to colored rectangles, rhombuses, and squares, from orchestrated collective movement that alternately expands and concentrates, hints at aggregation or disaggregation, from the contrast between particle and background, whether surface or material—canvas, paper, sisal, wire—to the initial monochromy—or rather acromy—to the near-neoplasticism of his latest reliefs. And it appears he has yet to exhaust its possibilities; new directions still lie ahead.

It is therefore no surprise that the relief seeks to experiment with three-dimensionality. This has been a recurring phenomenon since Cubism and has produced singular results in Brazilian art. When Lygia Clark called her articulated sculptures Bichos, she did not specify the animal. She simply used a more generic, abstract term. This is not the case with Piza’s work. The animal is the armadillo. I believe there could be no more fitting choice. Only it, and no other, could metaphorize the dynamics of Piza’s relief. The animal’s scaly, articulated, elastic, and flexible shell, composed entirely of small plates, mirrors the mobile, swift, metallic units of Piza’s reliefs. An animal living on the ground, burrowed, whose color blends seamlessly with the earth, appearing as organic as it is mechanical, practically a walking relief. The armadillo, ultimately, a solitary creature with unique autonomy, the living organic unit—uncertain, like life itself.

Indeed, by naming this three-dimensional work Tatu, Piza merely reaffirms the fundamental experience of his art: the relief now rises above the ground. For is the armadillo not the living particle inhabiting the primordial plane that is the Earth?

The name Tatu emerged almost without explanation, as if self-evident, because in the form of the animal, one plate lies atop another, between one and another, one over another. “My Tatu” is, at its core, the synthesis of a whole, simultaneously the path and the result of encounters, reunions, arrangements, disarrangements; it is an obsession, the necessity of occupying space.

In the compositions, forms hide and, because they are hidden, they create a sense of excitement, a desire to discover what lies beneath. They settle into space, almost autonomously, move toward the wall, and eventually exist within it. But both in the Tatu and in the compositions, the age-old story of being and non-being is woven—what has been, what is, what I wish had been, the forms I integrated and expelled at the corner of what was and what could come to be.

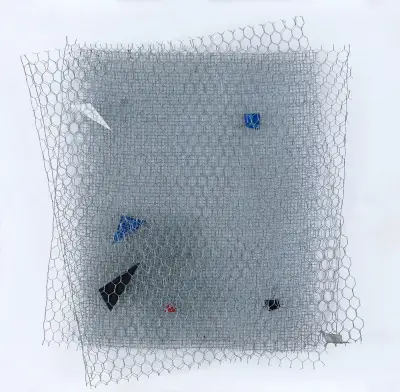

Relevant Weavings

For a long time, Arthur Luiz Piza has been mastering media, techniques, and materials—erudite or mundane, classical or banal, noble or vulgar—to create a contemporary dialogue. We have already seen, in his works, the precise use of doormats, pins, sand, wax, silver, porcelain, the optimized execution of prints, watercolors, paintings, collages, reliefs, and especially the promiscuity and subversion of all these elements. This time is no different: the artist has scaled industrial wire canvases that grid the horizon of large cities to collaborate with the already famous geometric entities that have inhabited his works for decades.

Now, the small, colorful beings continue to nestle within metallic structures formed by folds and/or superpositions of industrial fabric. These voluminous shelters equally host—and et pour cause—a myriad of paradoxical effects: the stacking of alternating layers among their components produces ambiguous readings of ancient questions still indecipherable.

The entanglements of highly polished stainless steel respond particularly to light without diminishing the optical performance of their colorful occupants. They resemble nebulae: luminous and translucent, the silver weavings create a shimmering mist that highlights the denser presences of the elements within, while respecting their hues: allies in the many ephemeral phenomena generated by the object.

The galvanized wrappings in darker tones, similarly inhabited by the same type of geometric creatures, generate a comparable set of curious visual disturbances. The darker mesh, more assertive than the silver, triggers intense contrast between the chromatic timbres of the two components. The notions of cooperation between them remain valid. Once again, we cannot decide between the cages and their occupants. The appearances of these works fluctuate with light and observation, full of configurations and considerations that confound us with the simultaneity of disciplined criteria. Yet, even though readings guided by the old "figure and ground" scheme may initially seem outdated in evaluating these works, the well-known freedom of Arthur Luiz Piza's objects allows—indeed demands—that one engage even with the old theme. Beyond that, it must be acknowledged: the plaques are the artist’s eternal divas, always the hostesses of his plastic jam sessions. It is impossible to assign ultimate superiority to any single element of the composition—cutouts or wire—an indiscretion not permitted by the hostesses.

ALP’s weavings not only accept explanatory descriptions but also invite conversation stemming from pure delight as a form of critical speculation. The artist speaks of the personal concerns that propelled the weavings, in a clarifying reduction that can extend to the totality of his production: My obsession is arranging and disarranging. In the weaving, I try to create, with the accumulation of wires, a field conducive to arranging my forms, sometimes on top, sometimes among different depths, arranging and disarranging them in that space, as if searching for the hidden. A way of capturing, holding, and securing free forms, which, once preserved or hidden, should maintain the tension inherent to them.

The drawings gathered under a single title—series "desenho tramas"—distinguished only by sequential numbering, present watercolor polygons distributed over a rhythmic mesh of black thread arabesques. Taut, the geometric figures surge toward us, piercing the two-dimensional space, detaching themselves from the nebula of hieroglyphs. These relief-drawings suggest intimacy, a casual, almost "performed" informality, so to speak. On a second glance, however, they vibrate in a cubist—or perhaps "formalist"—key, as has been noted. Later, they can reveal a third, poetic temperament, an anarchic behavior par excellence. Indeed, these hybrid objects signal the order of disorder and the disorder of order, and all else that may emanate human quality.

Demonstrating that size is no proof, Arthur Luiz Piza’s works highlight the complex relationship between scale and aesthetic dimension, skillfully maneuvering his lexicon between sophistication and simplicity: gestural ornamentation in ink, its uniform and rhythmic coverage, and the subtly irregular, semi-glued watercolor hues of geometric particles. The singularity flaunted by the artist is knowingly accompanied by a systematic, yet discreet, contravention of the main artistic and theoretical guidelines of the past century. These small works nevertheless summarize the liberating procedures, the articles that for decades have sustained Arthur Luiz Piza’s practice: The fact is, thinking about it, the watercolors are an important synthesis of my work, something that makes me reconsider everything I have done so far. (1)

Infusing the space with a freshness more suited to youthful ventures, strengthened by certainties gathered over the years, the artist presents the mature result of a syntactic elaboration guided by a mix of rebellion and discipline—perhaps the greatest legacy of modernity. Ultimately, this is a rare opportunity to witness a particularly daring poetics; the courage to present work so economically amidst the extravagance of contemporary abundance is audacious to the extreme. His works invite a tête-à-tête, in contrast to the desperate clamour of contemporary scale: who will shout louder than the rest of the world?

Solo Exhibitions

2008

Meu Tatu. Gabinete de Arte Raquel Arnaud, São Paulo, Brazil.

2006

Tramas. Gabinete de Arte Raquel Arnaud, São Paulo, Brazil.

Banco Real, ABN AMRO, São Paulo, Brazil.

Centro Cultural Instituto Moreira Salles, Belo Horizonte, Brazil.

Centro Cultural Instituto Moreira Salles, Poços de Caldas, Brazil.

2005

Instituto Moreira Salles, São Paulo, Brazil.

Galerie Jeanne Bucher, Paris, France.

Galeria 111, Lisbon, Portugal.

2004

Museu Murilo Castro, Belo Horizonte, Brazil.

Galeria Gestual, Porto Alegre, Brazil.

Instituto Moreira Salles, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

2002

Leveza e Matéria. Gabinete de Arte Raquel Arnaud, São Paulo, Brazil.

Reliefs 1958/2002. Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo, Brazil.

Centro Cultural Calouste Gulbenkian, Paris, France.

Atelier Georges Leblanc, Paris, France.

2001

Galerie Annie Lagier, Isle-sur-la-Sorgue, France.

2000

Instituto Moreira Salles, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Galeria Glemminge, Glemmingebro, Sweden.

1999

Instituto Moreira Salles, Belo Horizonte, Brazil.

Galeria 111, Porto, Portugal.

Galerie Jeanne Bucher, Paris, France.

Instituto Moreira Salles, Poços de Caldas, Brazil.

1998

Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña, Sala Mayor, Convento de los Dominicanos, San Juan, USA.

Centro Cultural Lezard, Colmar, France.

Instituto Moreira Salles, São Paulo, Brazil.

Galeria 111, Lisbon, Portugal.

1997

Musée Baron Gérard, Bayeux, France.

Galerie des Lumières, Nanterre, France.

1996

Galerie Annie Lagier, Isle-sur-la-Sorgue, France.

Gabinete de Arte Raquel Arnaud, São Paulo, Brazil.

Galerie Synthèse, Brussels, Belgium.

Galerie La Hune, Paris, France.

1995

Maison de l’Amérique Latine, Paris, France.

Artcurial, Paris, France.

Galerie Donath, Troisdorf, Germany.

1994

Museu da Gravura, Curitiba, Brazil.

Instituto Moreira Salles, Poços de Caldas, Brazil.

Galeria Mikimoto, Tokyo, Japan.

Galerie Annie Lagier, Isle-sur-la-Sorgue, France.

Galerie Braun, Wuppertal, Germany.

1993

Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo, Brazil.

Penta di Casinca, Corsica, France.

Art Fair, Seoul, Korea.

Galerie Hélios, Calais, France.

1992

Galerie Matarasso, Nice, France.

Contemporary Printmaking Center, La Coruña, Spain.

Galeria Yon, Seoul, Korea.

1991

Palácio da Abolição, Fortaleza, Brazil.

Galerie La Hune, Paris, France.

Artcurial, Paris, France.

1990

Fondation Carcan, Brussels, Belgium.

Galeria Pinax, Skellefteå, Sweden.

Museum of Art and History, Chambéry, France.

1989

Gabinete de Arte Raquel Arnaud, São Paulo, Brazil.

Galeria Tina Zappoli, Porto Alegre, Brazil.

Gesto Gráfico, Belo Horizonte, Brazil.

Galeria Banco Itaú, Ribeirão Preto, Brazil.

Galeria Tríade, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Galerie Annie Lagier, Isle-sur-la-Sorgue, France.

1988

Galerie La Hune, Paris, France.

Galeria Mikimoto, Tokyo, Japan.

1987

Galerie Djelall, Isle-sur-la-Sorgue, France.

Galeria Aeblegaarden, Copenhagen, Denmark.

1986

Gravura Brasileira, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Galeria 111, Lisbon, Portugal.

Museu de Arte do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil.

Gabinete de Arte Raquel Arnaud, São Paulo, Brazil.

Galerie La Hune, Paris, France.

1985

Artothèque de Montpellier, France.

1984

Galeria Aeblegaarden, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Galeria Mikimoto, Tokyo, Japan.

La Galeria, Quito, Ecuador.

Galerie La Hune, Paris, France.

1983

Gabinete de Arte Raquel Arnaud, São Paulo, Brazil.

Gravura Brasileira, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

1981

Galerie Bellechasse, Paris, France.

Galerie La Hune, Paris, France.

Museu de Arte de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil.

Gabinete de Arte Raquel Arnaud, São Paulo, Brazil.

Galeria Bacou, Tokyo, Japan.

Gravura Brasileira, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

1980

Galeria Madoura, Vallauris, France.

1979

Galeria Heimeshoff, Essen, Germany.

Centro de Ação Cultural de Montbéliard, France.

Galerie La Hune, Paris, France.

1978

Galeria Glemminge, Glemmingebro, Sweden.

1977

Galeria Shindler, Bern, Switzerland.

Galeria Arte Global, São Paulo, Brazil.

Galeria Mestre Mateo, La Coruña, Spain.

1976

Galeria Det Lille, Bergen, Norway.

Galeria MArte, Milan, Italy.

Galeria Lochte, Hamburg, Germany.

Galerie La Hune, Paris, France.

Galeria Mebius, Gothenburg, Sweden.

Galeria Panarame, Wiesbaden, Germany.

1975

Galerie La Taille Douce, Brussels, Belgium.

1974

Galerie Suzanne Egloff, Basel, Switzerland.

Galerie Schmucking, Dortmund, Germany.

Petite Galerie, São Paulo, Brazil.

Petite Galerie, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

1973

Galerie Schindler, Bern, Switzerland.

Galerie Turuvani, Neuveville, Switzerland.

1972

Galerie Heimeshoff, Essen, Germany.

São Paulo Museum of Art, Brazil.

1971

Galerie Leandro, Geneva, Switzerland.

1970

Galerie Paul Bruck, Luxembourg.

Novo Art, Gothenburg, Sweden.

1969

Galerie Taille Douce, Brussels, Belgium.

Galerie du Fleuve, Bordeaux, France.

Galerie Harmonies, Grenoble, France.

Galerie La Hune, Paris, France.

1968

Galerie Gabriel, Mannheim, Germany.

Galeria Cosme Velho, São Paulo, Brazil.

1967

Galerie Bonino, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

1966

Galerie Horne, Luxembourg.

1965

Galerie La Hune, Paris, France.

1964

Graphic Arts Gallery, New York, USA.

1963

Galerie Schmucking, Braunschweig, Germany.

Galerie La Hune, Paris, France.

1962

Galerie Mala, Ljubljana, Yugoslavia.

Frankfurt Kunstkabinett, Frankfurt, Germany.

1961

Galerie La Hune, Paris, France.

1960

Grafisches Kabinett Weber, Düsseldorf, Germany.

1959

Galerie La Hune, Paris, France.

Museum of Modern Art, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

1958

Museum of Modern Art, São Paulo, Brazil.

Group Exhibitions

2010

Large Formats, Great Artists. Gabinete de Arte Raquel Arnaud, São Paulo, Brazil.

2009

Limited Editions of Mondrian and Piza. Gabinete de Arte Raquel Arnaud, São Paulo, Brazil.

2007

Entre Deux Lumières – Brazilian Artists in France. Brazilian Embassy, Paris, France.

Selective Gaze. Gabinete de Arte Raquel Arnaud, São Paulo, Brazil.

2005

5th Mercosur Biennial, Porto Alegre, Brazil.

Experiences at the Frontier. Gabinete de Arte Raquel Arnaud, São Paulo, Brazil.

Art in the Metropolis. Instituto Tomie Ohtake, São Paulo, Brazil.

2004

Metrópolis Contemporary Art Collection. Espaço Cultural CPFL, Campinas, Brazil.

Transitive Modernity. Museum of Contemporary Art, Niterói, Brazil.

Gabinete de Papel. Centro Cultural São Paulo, Brazil.

São Paulo SP – Gesture and Expression: Informal Abstraction in the JP Morgan Chase and MAM Collections. Museum of Modern Art of São Paulo, Brazil.

2003

Arco/2003, Parque Ferial Juan Carlos I, Madrid, Spain.

Humanities. Galeria Tina Zappoli, Porto Alegre, Brazil.

Projeto Brasilianart. Almacén Galeria de Arte, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Treasures from Caixa: Brazilian Modern Art in the Caixa Collection. Conjunto Cultural da Caixa, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Printmaking Goes Well, Thank You: Historical and Contemporary Brazilian Prints. Espaço Virgílio, São Paulo, Brazil.

Arco 2003. Gabinete de Arte Raquel Arnaud, São Paulo, Brazil.

Lauro Eduardo Soutello Alves Collection at MAM. Museum of Modern Art of São Paulo, Brazil.

MAC USP 40 Years: Contemporary Interfaces. Museum of Contemporary Art, USP, São Paulo, Brazil.

2002

Le Signe et la Marge. Musée d’Art Moderne Richard Anacréon, Granville, France.

2001

Salón de Mayo, Paris, France.

Young Contemporary Printmakers, Antony, France.

2000

Sarcelles Biennial, France.

Puerto Rico Biennial, San Juan, Puerto Rico.

Salón de Mayo, Paris, France.

1999

Norwegian International Print Triennial, Fredrikstad, Norway.

Sarcelles Biennial, France.

Salón de Mayo, Paris, France.

Young Contemporary Printmakers, Antony, France.

1997

International Graphic Arts Exhibition. City Art Museum of Sakaide, Kagawa, Japan.

Salón de Mayo, Paris, France.

Young Contemporary Printmakers, Antony, France.

1996

1st International Biennial of Works on Paper. Tolentino, Italy.

Salón de Mayo, Paris, France.

1995

Salón “Realités nouvelles”, Paris, France.

Young Contemporary Printmakers, Antony, France.

Norwegian International Print Triennial, Fredrikstad, Norway.

1994

Salón de Mayo, Paris, France.

1993

Triennale of the Americas, Maubeuge, France.

French Painter-Printmakers. Orangerie du Luxembourg, Paris, France.

Roularta Group. Research Center, Zellik, Belgium.

The Art of Printmaking. Château de Reviers, France.

Salón de Mayo, Paris, France.

1992

Latin American Art – 1911-1992. Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, France.

Norwegian International Print Triennial, Fredrikstad, Norway.

Puerto Rico Biennial, San Juan, Puerto Rico.

Salón “Réalités nouvelles” (also 1960–1974), Paris, France.

Salón de Mayo, Paris, France.

1991

5th Contemporary Print Biennial, France.

Salón de Mayo, Paris, France.

Young Contemporary Printmakers, Antony, France.

1990

International Graphic Arts Exhibition, Fresen, Germany.

Sarcelles Biennial.

Puerto Rico Biennial, San Juan, Puerto Rico.

International Print Biennial, Vico Arte, Vico, Italy.

Latin American Art, Germany.

Salón de Mayo, Paris, France.

1989

Homage to Piza. Niort Biennial, France.

Landskrona Konsthall, Sweden.

Salón de Mayo, Paris, France.

Norwegian International Print Triennial, Fredrikstad, Norway.

1988

Latin Visions, Latin Union, Lisbon, Portugal.

Salón de Mayo, Paris, France.

Puerto Rico Biennial, Puerto Rico, USA.

1987

For Another Print. Petit Théâtre, Asnières, France.

Panorama of the Contemporary French School, Tel Aviv, Israel.

1986

Latin America. IILA – Italian-Latin American Institute, Rome, Italy.

2nd Havana Biennial, Cuba.

Puerto Rico Biennial, Puerto Rico, USA.

For Another Print. Cultural Centers of Compiègne and Noyon, France.

French Painter-Printmakers. National Library, Paris, France (since 1982).

Salón de Mayo, Paris, France.

1985

Triennial of Grenchen, Switzerland (since 1958).

Première Exposition Européenne de Création. Grand Palais, Paris, France.

Salón de Mayo, Paris, France.

1984

1st Havana Biennial, Cuba.

Puerto Rico Biennial, Puerto Rico, USA.

Young Contemporary Printmakers, Antony, France.

1983

100 Latin American Artists. Cultural Centers of Compiègne and Amiens, France.

Latin America. Grand Palais, Paris, France.

Latin America. P. Payle Cultural Center, Besançon, France.

Young Contemporary Printmakers, Antony, France.

1982

Sèvres Manufacture. National Museum, Stockholm, Sweden.

Sèvres Manufacture. Museum of Industrial Art, Oslo, Norway.

International Art of Kyoto, Japan.

Puerto Rico Biennial, Puerto Rico, USA.

1981

2nd European Print Biennial, Germany.

Salón de Mayo, Paris, France.

International Print Exhibition. Ljubljana, Yugoslavia.

Young Contemporary Printmakers, Antony, France.

1980

The Crafts of Art. Museum of Decorative Arts, Paris, France.

2nd Ibero-American Biennial, Mexico City, Mexico.

Salón de Mayo, Paris, France.

Norwegian International Print Triennial, Fredrikstad, Norway.

1979

Printmaking Today. National Library, Paris, France.

International Print Exhibition, Ljubljana, Yugoslavia.

1978

International Drawing Exhibition. Rijeka, Yugoslavia.

International Drawing Festival. Christchurch, New Zealand.

Norwegian International Print Triennial, Fredrikstad, Norway.

1976

French Ceramics. Museum of Modern Art, Seoul, Korea.

French Ceramics. Hermitage Museum, Leningrad, USSR.

Norwegian International Print Triennial, Fredrikstad, Norway.

1975

Salón de Mayo, Paris, France.

International Print Exhibition. Ljubljana, Yugoslavia.

1974

Kraków Biennial, Poland.

School of Fine Arts, Angers, France.

Sèvres Manufacture. Palais du Congrès, Marseille, France.

Sèvres Manufacture. Amos Anderson Museum, Helsinki, Finland.

Salón de Mayo, Paris, France.

1972

Kraków Biennial, Poland.

Salón de Mayo, Paris, France.

Norwegian International Print Triennial, Fredrikstad, Norway.

1971

Graphik der Welt. Nuremberg, Germany.

Salón de Mayo, Paris, France.

1970

White Itineraries. Museum of Art, Saint Etienne, France.

Kraków Biennial, Poland.

Menton Biennial, France.

1969

International Print Exhibition. Ljubljana, Yugoslavia.

1968

Art Vivant. Fondation Maeght, Saint Paul de Vence, France.

Menton Biennial, France.

Salón de Mayo, Paris, France.

Kraków Biennial, Poland.

1967

Vancouver International Print Exhibition, Canada.

International Print Exhibition, Ljubljana, Yugoslavia.

1966

Kraków Biennial, Poland.

Venice Biennial, Italy.

1964

Fifty Years of Collage. Museum of Decorative Arts, Saint Etienne, France.

Fifty Years of Collage. Museum of Decorative Arts, Paris, France.

1963

Paris Biennial, France.

São Paulo Biennial, São Paulo, Brazil.

Kristianstads Museum, Sweden.

1962

École de Paris. Galerie Charpentier, Paris, France.

1961

Paris Biennial, France.

Relief. Galerie du XXème Siècle, Paris, France.

Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

1960

Brazilian Artists. Bezalel Museum, Jerusalem, Israel.

1959

Documenta, Kassel, Germany.

São Paulo Biennial, Brazil.

International Print Exhibition, Ljubljana, Yugoslavia.

1957

Salón de Mayo, Paris, France.

São Paulo Biennial, Brazil.

International Print Exhibition, Ljubljana, Yugoslavia.

1955

São Paulo Biennial, Brazil.

1953

São Paulo Biennial, Brazil.

1951

São Paulo Biennial, Brazil.

Awards

1994

Grand Critics’ Prize, São Paulo, Brazil.

1990

Printmaking Prize, Puerto Rico Biennial, USA.

1980

Jury Prize, Print Biennial, Norway.

Printmaking Prize, 2nd Ibero-American Biennial, Mexico.

1978

Acquisition Prize, Curitiba, Brazil.

1970

Printmaking Prize, San Juan Biennial, Puerto Rico.

Gold Medal, 2nd Print Biennial, Florence, Italy.

Special Mention for Art Book, Book Fair, Nice, France.

Printmaking Prize, 3rd Kraków Biennial.

1966

Printmaking Prize, Havana, Cuba.

Printmaking Prize, Santiago, Chile.

David Bright Prize, Venice Biennial, Italy.

1965

Printmaking Prize, 4th International Exhibition, Ljubljana, Yugoslavia.

1961

Printmaking Prize, 2nd Grenchen Triennial.

1959

Grand National Print Prize, 5th São Paulo Biennial, Brazil.

1953

Acquisition Prize, 2nd São Paulo Biennial, Brazil.